America’s highest ranking Democrat in the House of Representatives, Hakeem Jeffries, recently made his presence known with his inaugural address in this role, a poetic A to Z inventory of values that inspires or schools, depending on how the listener feels about democracy and decency. Intrigued like millions of others who have since viewed the speech, I was curious to learn more about Rep. Jeffries, and for me, that meant taking a dive into his genealogical past. For others who might share my curiosity, here are a few of the discoveries my research turned up:

1. Surnames adorning the branches of his family tree include Binford, Brooks, Carter, Cephas, Cooke, Fears, Foster, Gomes, Graca, Gross, Hobson, Jeffries, Pereira, Pina, Smith, and Taylor, so if you have any in common, you could be related.

2. You might think the odds of a connection are slim, but Congressman Jeffries has a multitude of cousins. One of his great-great-grandmothers made it to the century mark and her obituary noted that she left 77 great-grandchildren and 31 great-great-grandchildren. This was half a century ago, so the number of descendants from this ancestor alone would be in the hundreds by now. And in case you’re wondering, Hakeem Jeffries’ life overlapped hers, so he was one of those 31 great-greats.

3. While he was born in Brooklyn, his roots are planted elsewhere. Using the generation of his great-grandparents as a reference point, Virginia claims 3/8ths of his heritage, Georgia 1/4, Cape Verde 1/4 (more on this later), and Maryland 1/8. A combination of the Great Migration and immigration added California, Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, and Ohio into the mix.

4. A sad affair that emerges with distressing frequency in his family is parents dying young, particularly mothers. For instance, his mother’s mother, Nellie, died when she was only 23 years old and her daughter all of two. For Nellie’s husband, this would have been history repeating itself in the worst possible way, as his own mother had died at 23 when he was only two.

On his father’s side of the family, his grandfather — the youngest of 13 — was orphaned at 10. Due to these tragic losses, older sisters and aunts have played an outsized role in the family, stepping in to raise the children who have lost parents. When Jeffries’ parents married, for example, it was his mother’s aunt who announced their engagement.

5. A more welcome pattern that surfaces when researching Rep. Jeffries’ family tree is one of service to others — a blend of community, military, and union-related. His paternal grandmother was recognized by Essex County, New Jersey for her volunteer efforts helping elderly people who lived alone, while one of his maternal great-grandfathers helped the Mine, Mill & Smelter union he belonged to (which presumably assisted him when he later broke his leg at work).

His maternal grandfather was career military, enlisting in the Army during WWII in 1942 and serving until 1963, and his service may well be what inspired his daughter — Jeffries’ mother — to become chairman of the Junior Girls of both local and state American Legion Auxiliary posts. A newspaper article notes that she was the “first Negro girl ever” to serve in this capacity, a phrase that simultaneously makes one wince and appreciate that even to volunteer, she had to break new ground while still a teenager. Around the same time, she was also an officer with her school’s Future Teachers of America and Choir organizations, the latter especially fitting since she’s a gifted vocalist.

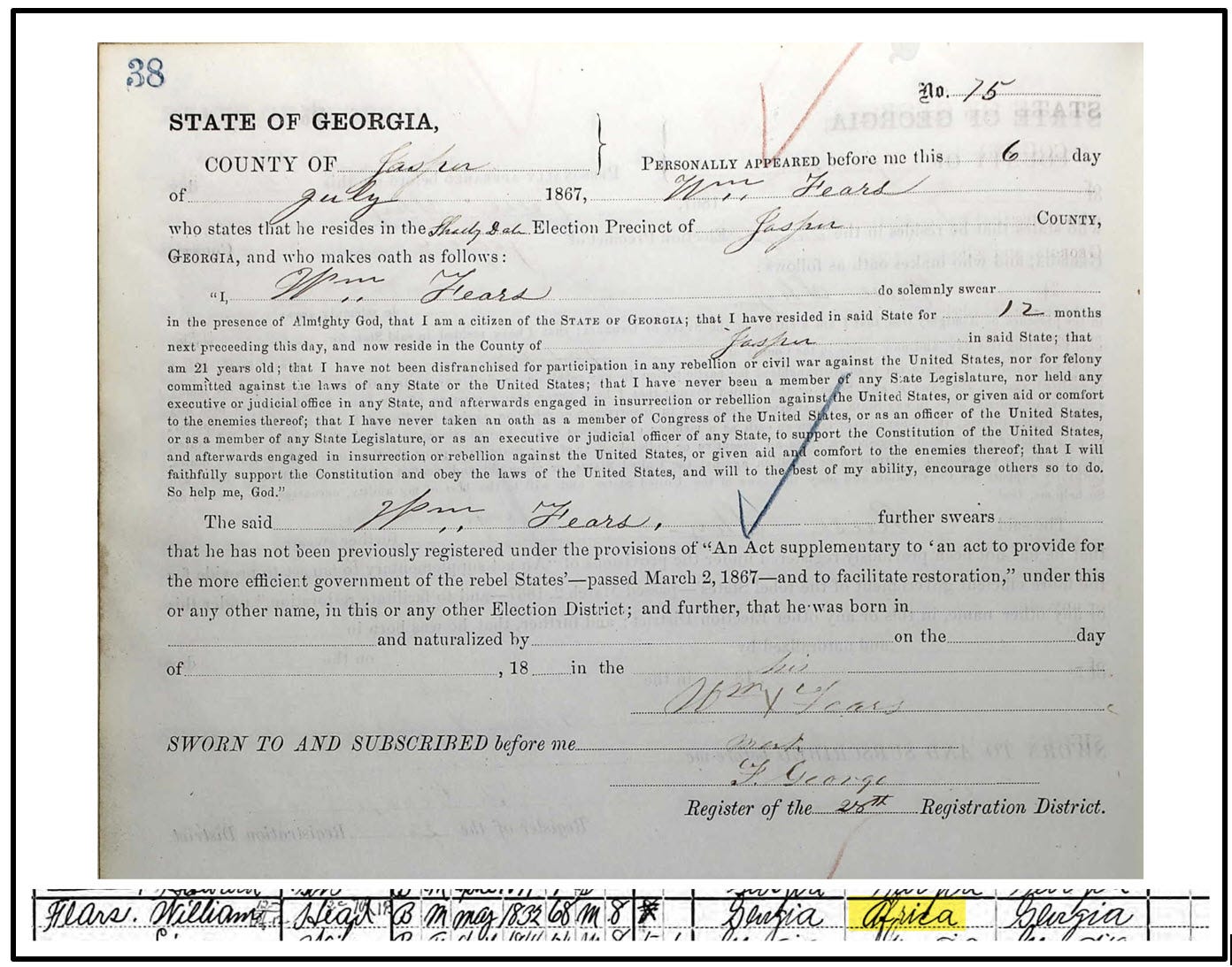

6. The Jeffries branch of the family hails from Jasper County, Georgia, and the earliest ancestor I’ve been able to find there so far is a 3rd great-grandfather named William Fears who was enslaved for the first forty or so years of his life. For this reason, July 6, 1867 would have been a special day for him. This was the date he registered to vote.

(both found on Ancestry)

A census record reveals that he had been born to a local woman and a father from Africa, so it must have seemed improbable to him that this moment would ever come.

Even so, Jasper County would not have been a haven for Fears and his family as a gently disguised form of slavery persisted there well into the 20th century. A Kirkus Review of Gregory A. Freeman’s eye-opening book, Lay This Body Down: The 1921 Murders of Eleven Plantation Slaves, summarizes this peonage system as follows: “A young black man would find himself arrested for some minor offense and issued a fine that he would be unable to pay; a local farmer would pay his fine and put him to work under slavery-like conditions, ostensibly to pay off this unasked-for loan.”

Lynchings and other forms of violence were also a constant threat. Jeffries’ ancestors — William Fears’ descendants — would finally leave in the early 1920s. In the half-decade leading up to their departure, at least 15 Black people had been lynched or otherwise murdered in the county.

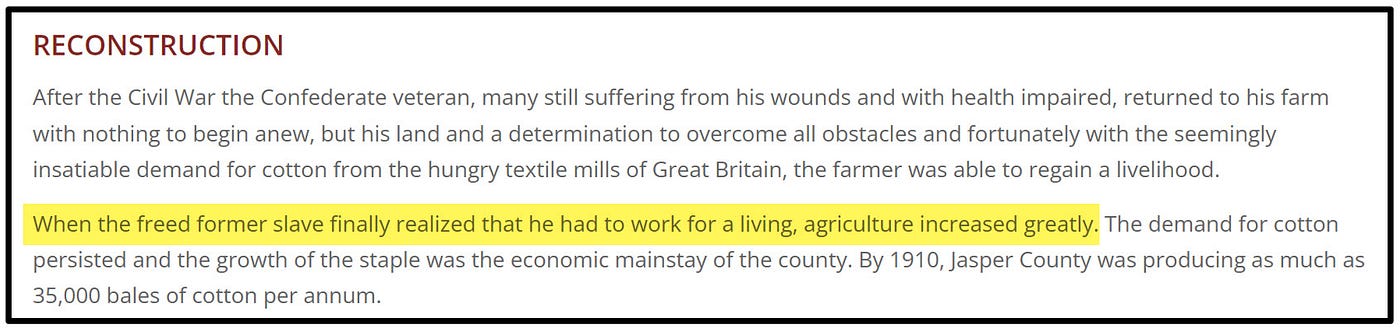

Jasper County history excerpt

None of this is included in this Jasper County history I came across in the course of my research — not surprising since it was written in 1969 and reflects perspectives and attitudes shared by many at the time. But it’s disconcerting that this is the history presented on the county’s official website today.

7. Finally, though most of Congressman Jeffries’ family tree meanders back for generations in the U.S., one portion came here just slightly over a century ago when a pair of his great-grandparents immigrated from Cape Verde (then a Portuguese colony), off the coast of West Africa.

His great-grandfather, Manuel Gomes, arrived in 1915 following the 4,000 mile path between Fogo and New Bedford, Massachusetts crossed by countless others since New England whalers had forged the connection back in the late 18th century. He married, had a son, applied for citizenship, and lost his wife — all by 1923.

Still, he carried on, working in brass mills and for a railroad, raising his son, securing his American citizenship, remarrying, and having more children. At some point, he returned home for good and died in São Filipe in 1974, where his grave can be seen today.

(FindaGrave, photo by Alan and Linda Martineau)

In his waning days, I can’t help but wonder if Manuel could have possibly imagined that Cape Verde would gain its independence just seven months later, much less that his then-four-year-old great-grandson, Hakeem Jeffries, would rise to where he is in the U.S. Congress today.

Top Photo: Hakeem Jeffries (official portrait, 2022)

Leave A Comment