When it comes to genealogy, I prefer fresh territory, which is why I usually avoid the mega-famous. If someone is universally renowned, it’s a given that hundreds, if not thousands, have already poked around the branches of their family tree, so what’s left to discover?

But on the few occasions I’ve gone ahead anyway, I’ve almost always wound up tripping across neglected or hidden pockets of ancestry, so when a journalist friend reached out with a specific request involving Taylor Swift, I agreed. I admire the hell out of her, so why not?

As is my habit, I started from scratch (too much sloppy research floating out there online that can lead you astray), and it didn’t take long to answer his question. That should have been the end of it, but an intriguing ancestor — the genealogical equivalent of a shiny object — had grabbed my attention and I had to know more.

In this case, it was a colorful great-grandfather who made me dig deeper, but once I did, it was his mother and his mother’s mother I couldn’t get enough of. And while it wasn’t Taylor’s beloved grandmother Marjorie’s branch, it was the one that had produced a man worthy of her.

Shiny Object Ancestor

So why did this particular great-grandfather make me do a double take? Well, his name was George Finlay, but sometime in his twenties, he appended the name of Lancelot. After that, he mostly went by Lance.

That raised an eyebrow.

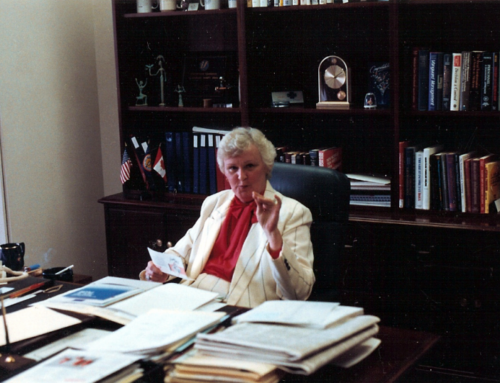

George Finlay in his late 50s circa 1932 (New York, U.S. District and Circuit Court Naturalization Records, 1824–1991, FamilySearch)

Before long, I found a record that said he had been born at sea. OK, this was becoming more interesting.

As I followed his paper trail, though, I found five documents citing an “at sea” birth, but another ten saying England and a further five stating Scotland. Hmmm…did he have something to hide? Given that he bounced around New Jersey, Ohio, Florida, New York, Rhode Island, and — oh, yeah, Trinidad and maybe Cuba — it was certainly a possibility.

Then there were his four wives, the last of whom — the keeper — would become Taylor’s great-grandmother. Seems Lance was a turn-of-the-(last)-century player.

And those first three wives came equipped with their own stories. One was born in Florida in the 1860s to a Polish father. That might not strike you as odd, but to put into perspective how unusual that would have been, only 20 Polish-born men lived in Florida around the time of her birth. Another wife had a brother who infuriated the family by leaving the bulk of his fortune ($300,000 in 1936 or roughly $6.6 million today) to British soldiers blinded and wounded in World War I — quite a surprise since they had immigrated to the United States almost 60 years earlier. This wife also had a child with Lance, so whether he knew it or not, Taylor’s grandfather had a half-sibling about 20 years his senior. And the last of this trio of wives had another husband who created the Museum of the American Indian (now part of the Smithsonian) and yet another who died in an “industrial accident” when mauled by a lion on a Los Angeles movie set.

Born Adrift?

These earlier wives offered fun diversions for a curious genealogist, but let’s get back to that “at sea” birth. I had 20 records with competing places of birth: Scotland, at sea, and England (sometimes specified as Southampton).

Scotland, I gradually realized, was a bit of an obsession with Lance. He wasn’t born there, but wrongly thought his father — who turned out to be from a well-to-do family in Ireland — was. He also claimed to have obtained his education at the University of Glasgow, though I couldn’t find his name among graduates of that era. It’s clear that he possessed considerable engineering expertise, even securing a patent, so perhaps he had studied there, but not finished? Whatever the case, I could eliminate Scotland as his place of his birth.

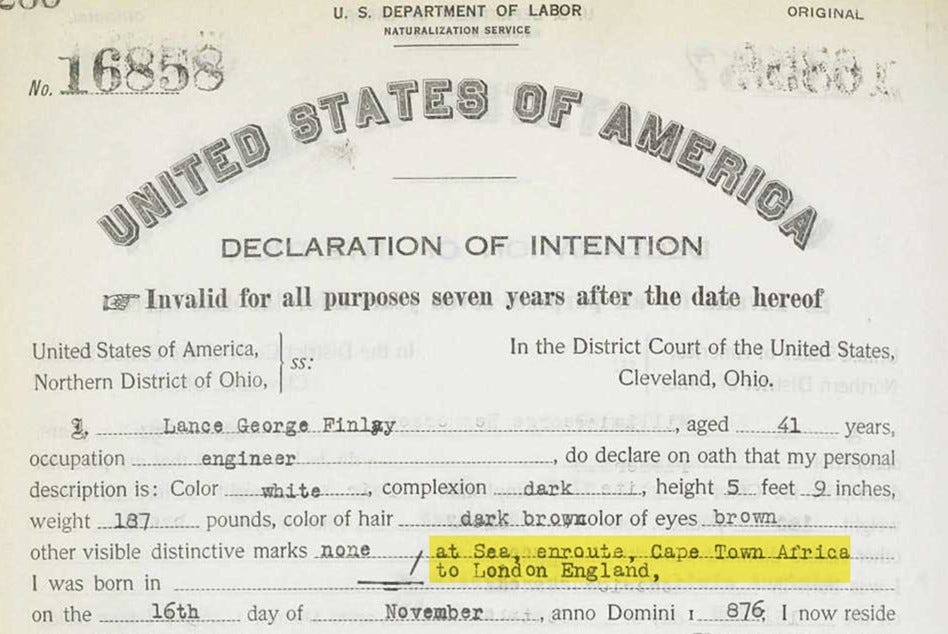

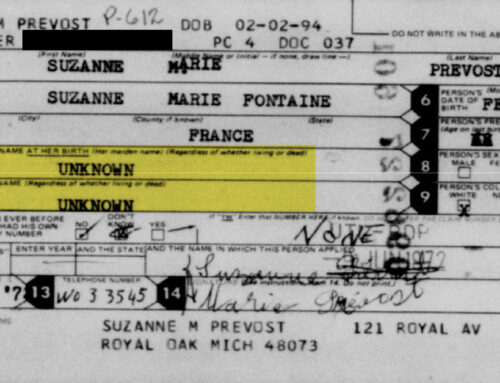

Declaration of Intention for Lance George Finlay. Among other things, it reveals that he was 5’9” and 187 pounds with dark hair and complexion, and brown eyes. (U.S. District Court for the Eastern Division of the Northern District of Ohio. FamilySearch)

Half of the documents cited England, and I did indeed find a birth certificate for him in Southampton, but that didn’t rule out the possibility of his having been born at sea. His November 16th birth wasn’t registered until December 31st, and U.K. sea births from 1854 on were supposed to be filed on ships’ logs and again on land after docking. I’ve searched Marine (and foreign birth) collections available online and nothing pops out, and yet, by the time I tripped across a declaration of intention (to become a citizen on the United States) specifying that his birth occurred “enroute, Cape Town, Africa to London, England,” it was exactly the navigational crossing I was expecting. And that was because of his mother, Emma.

Unshakable Emma

Emma Maria Williams was English, but only spent about three years of her first three decades in England. In fact, she began life in Malta. Born on the 18th of January in 1843, she joined a naval family as their only daughter.

It’s doubtful she remembered much about Malta, as her family returned to Stoke Damerel (now essentially a part of Plymouth in Devonshire, now known as Devon) — where her parents were originally from — when she was about four or five. That’s where the 1851 census found her with her “seaman’s wife” mother and little brother. Her father was absent, typical in such families.

When she was about eight, her family picked up again and moved to Simon’s Town, South Africa — slightly south of Cape Town.

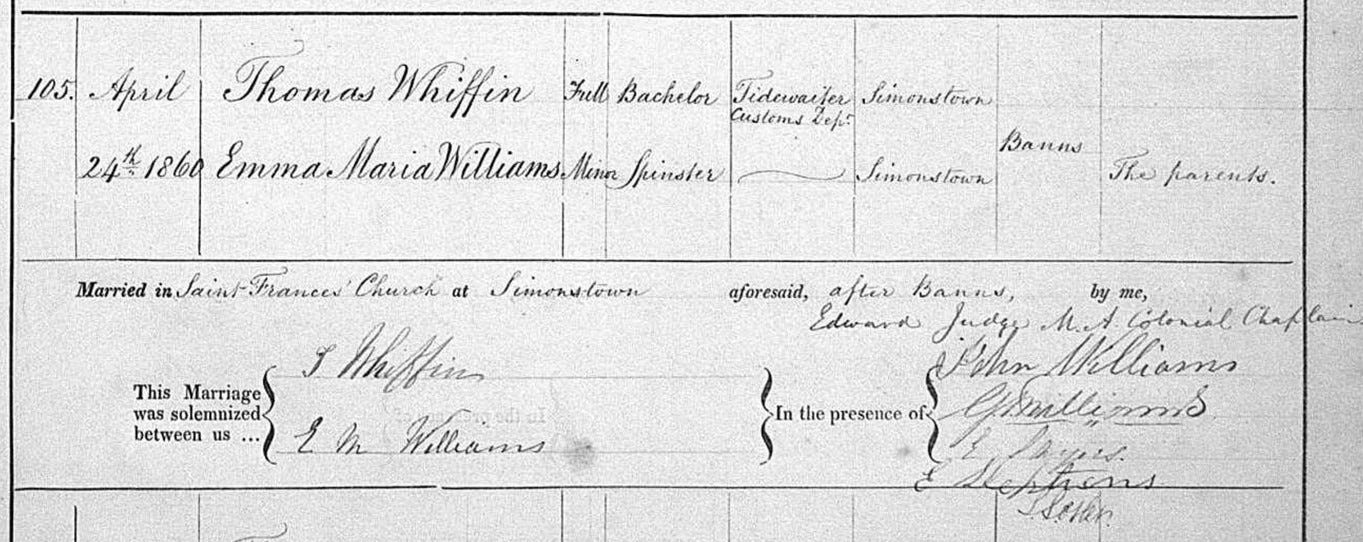

Marriage of Thomas Whiffin and Emma Maria Williams in Simon’s Town, South Africa, 24 April 1860 (Church of the Province of South Africa, Parish Registers, 1801–2004, FamilySearch)

At the age of 17, Emma married Thomas Whiffin, about ten years her senior. Thomas was a tidewaiter, a Customs official who boarded ships upon arrival to enforce regulations. This combination of naval and Customs work contributed to generations of meandering in the family, and while there were plenty of people traipsing the globe on behalf of the British Empire back then, that doesn’t diminish the hardship of such journeys in the 19th century. Emma’s life, while not an easy one, was representative of this portion of Taylor’s family tree that seems to have injected wanderlust into her gene pool, a trait she apparently inherited.

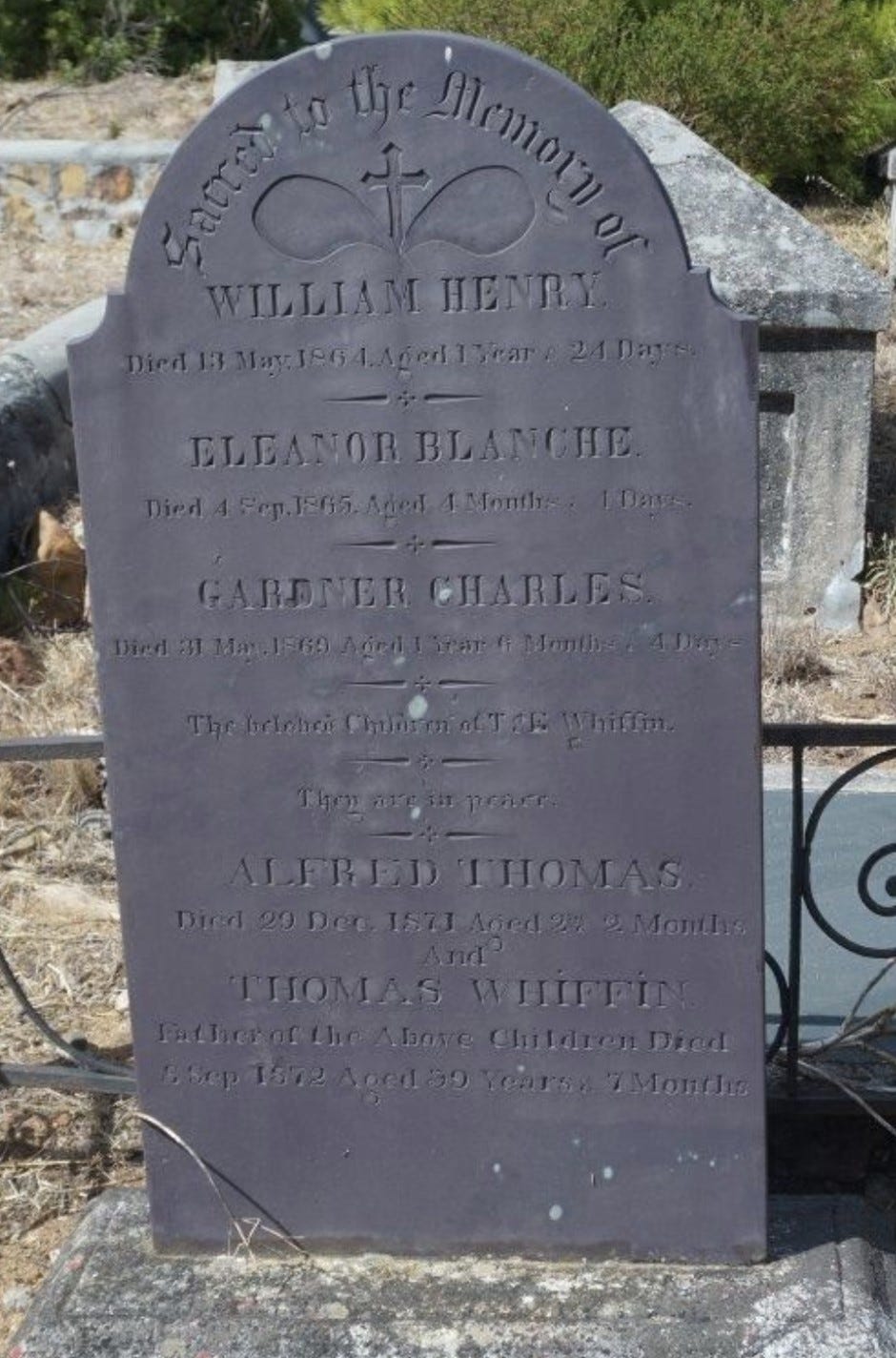

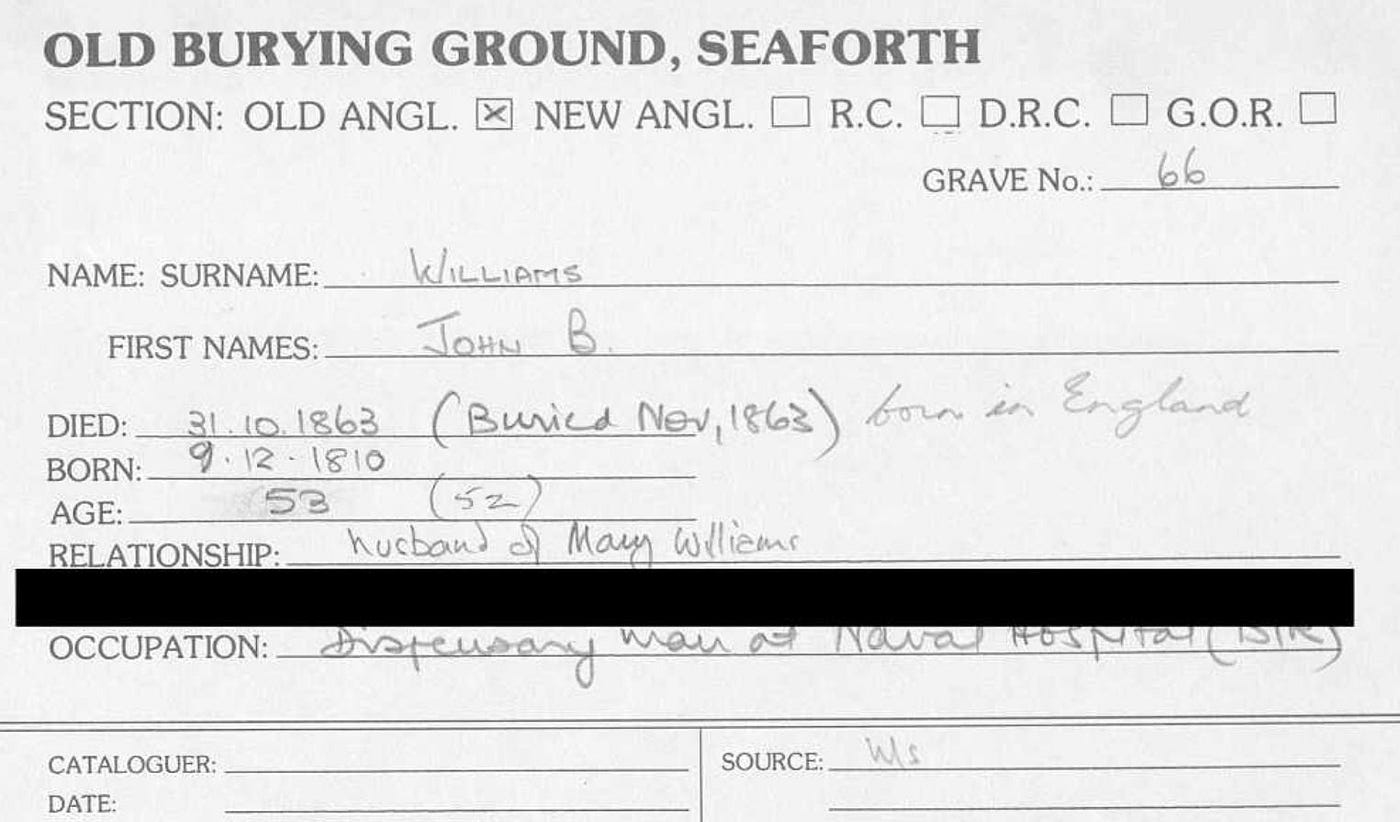

During the first decade of married life, Emma adhered to the usual pattern at the time, giving birth like clockwork every other year — 1861, 1863, 1865, 1867, and 1869 — but she never had more than two children alive at once because all but her eldest died by the age of 26 months. After a brief gap, she had another child in 1873, which would have been cause for celebration — that is, if her husband hadn’t died four months earlier. This brutal series of losses is captured on a tombstone for her husband and their four babies in the Seaforth Old Burying Ground and Garden of Remembrance.

Tombstone of Thomas Whiffin and four of his and Emma’s children (used with kind permission of Peter H) (Find a Grave memorial for Thomas Whiffin (1833–1872), Memorial ID 197256778, Seaforth Old Burying Ground and Garden of Remembrance, Seaforth, City of Cape Town Metropolitan Municipality, Western Cape, South Africa; Maintained by Peter H, contributor 47423563)

So ten days past her 30th birthday, Emma found herself widowed with a tween and an infant. It’s not a stretch to imagine that the saving grace that kept her from floundering was having her mother and a few brothers nearby in Simon’s Town. She at least had some support, but then two years later, her mother died.

This might have been what caused her return to England, a country she had spent so little time in, but there was another factor at play: Emma was pregnant again. The father was a naval officer from a posh family named George Finlay, and the hint that he was the instigation is that she went to Hampshire, where he was from, rather than Devonshire, where her own family had its roots.

Whether they married or not is unclear. I haven’t found a record, but that’s not unusual with couples on the move, and there’s conflicting evidence (such as when George married another woman several years later claiming to be a bachelor). Regardless, Emma moved to his home base in England, used the Finlay surname for about a decade, and named their son after him, so whether there was a wedding or not, there was undoubtedly an expectation of one.

And yes, the timing suggests that Emma may well have given birth at sea “enroute, Cape Town, Africa to London, England” as noted in one of George Jr.’s (aka Lance’s) documents. Even if she made it to land before delivering, she had made the long voyage very pregnant.

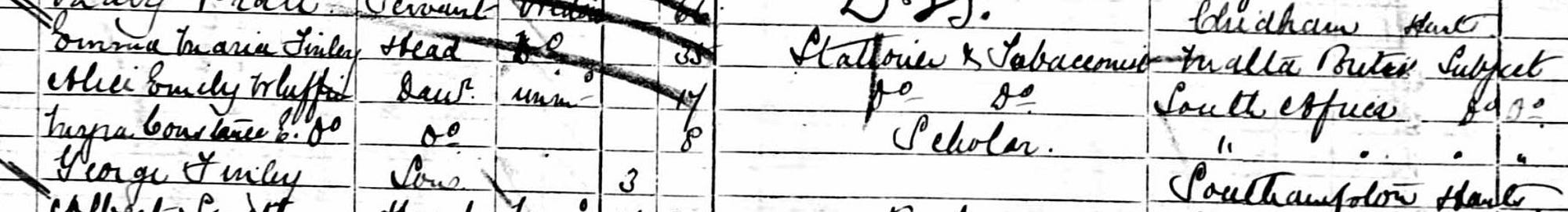

Then she was left on her own in a place she had never lived, but Emma was resourceful. The 1881 census found her living in Portsea supporting her son and two daughters as a stationer and tobacconist.

1881 census for Emma and her family (U.K. Public Record Office as seen on Ancestry)

Portsea rang a bell so I consulted some research I did years ago and was amused to find Taylor’s ancestors living midway — about a mile in each direction — between a pair of Biden families who are related to our President. Cue the next wacky conspiracy theory about Joe Biden and Taylor Swift’s relatives of yore getting together in a Portsea pub in the 1880s to orchestrate the outcome of the 2024 U.S. Presidential election!

Returning to Emma, her sorrows still weren’t over as she lost yet another child in 1887 leaving her with her Finlay son and a daughter who was now the last survivor from her first marriage. But there were also some gentle consolations. She had given up on George Finlay (Sr.), relocated to Devonshire, her own family’s home county, and found companionship by remarrying — this time to a Navy instructor named George Downer. Theirs was a happier union as they stayed together until his death. She lived another decade, finally passing away at 66.

You already know what became of her son, and as I write these words, Taylor is performing in Sydney, Australia, so it’s worth mentioning that her remaining daughter’s descendants eventually settled in New South Wales, meaning that odds are good there are cousins in the crowd.

Emma Maria (Williams) Whiffin Finlay(?) Downer, Taylor’s future great-great-grandmother, was made of sterner stuff. Born into a seafaring family and bouncing around Malta, England, and South Africa, she was an early globetrotter. A mother of seven, she endured the agony of watching five of her children go to untimely graves. Widowed young, and a few years later, abandoned in a country she had only resided in briefly as a child, she never stopped and somehow found a way to just keep cruisin’. And at least some of her remarkable fortitude was attributable to her own mother.

Like Mother, Like Daughter

Mary Ann Newcombe was born in Plymouth, England around 1812, and in 1830, married a mariner named John Benjamin Williams. She and John had five children over two decades — more spaced out than most due to the amount of time he spent at sea, a notion supported by his Royal Navy allotment declarations. So Mary Ann was married, but for frequent stretches would have felt like a single mother. That said, she would have had the comfort of this also being true of many of her neighbors.

Sometime around 1840, her husband’s career caused the family to move to Malta. As best as I’ve been able to ascertain, they lived in or near Sliema. It was here that she would give birth to her only daughter whose story you’ve just learned, but not before losing her first-born. Eight-year-old John Benjamin was buried in Malta in 1842 while his father was serving as Master of the HMS Media.

Death of Mary Ann and John’s first-born (Malta Family History — with thanks to avid genealogists who generously placed this information online and to the WaybackMachine for preserving it)

The family later returned to England for a few years before shifting once more to South Africa sometime between April 1851 and May 1852. This narrow time frame means that Mary Ann likely made the journey pregnant since she gave birth to her last child in Simon’s Town in early June of 1852. Though she’d have no way of knowing it, she was setting an accidental precedent for her daughter’s at-sea experience a couple of decades later.

In spite of events in South Africa at the time, the period that followed was probably the most settled portion of Mary Ann’s life. She had her children with her and even her husband, as he took a hospital dispensary position, presumably so they could all be together. Simon’s Town would have been quieter than they were used to, but with moments of excitement such as Emma’s wedding in 1860 and later that same year when Queen Victoria’s son, Prince Alfred, arrived. He served in the Navy and was the first member of the royal family to visit South Africa. Some locals wanted to mark the occasion by changing the name of their community to Alfred’s Town, but Simon managed to hold his own.

This interlude ended when her husband died in 1863. This left her with two sons, ages 11 and 16, at home, but her older children were married and living in the area, so she wasn’t entirely on her own. At this point, Mary Ann could have opted to go to England, but decided instead to spend the rest of her life in Simon’s Town, where she would be buried with her husband a dozen years later.

Burial record for John B. Williams (Cape Province, South Africa Cemetery Records, 1886–2010, FamilySearch)

Mary Ann and John’s wandering ways from the 1830s to the 1850s set a pattern in the family going forward — one that can be illustrated by logging the places of birth and death of their five children. Notice that no two of their children share the same birth-death country pairing.

As we’ve already seen, the oldest died as a youngster in Malta, and Emma went back to England. So did the youngest son, Walter, but not before he had spent a long career in Customs in China. Because of him, Taylor has a family member buried in Hong Kong as his first wife sadly died there.

Tombstone of Annie Williams, wife of Walter (Hong Kong Memory, courtesy of Patricia Lim)

The other two sons stayed in South Africa, meaning that Taylor also has kin there. Then again, some of their descendants dispersed adding Northern Ireland, Kenya, and Guernsey in the Channel Islands into the mix. So thanks to her second and third great-grandmothers, Taylor’s relatives may not be quite as widespread as Swifties, but it’s not for lack of trying. Give ’em another generation or two and there’ll be cousins in every audience! And now that their stories have been shared, may their adventurous and resilient ancestors, Mary Ann and Emma, always be remembered.

Leave A Comment