She came from a gold-obsessed family, so perhaps it wasn’t so surprising when the treasure bag was found in Hannah’s water closet, but what was this Galway girl even doing in San Francisco?

Anyone who’s ever dabbled in genealogy knows that certain forebears call louder than others – even when they’re not your own. While researching Katheryn Elizabeth Hudson – better known as musical megastar, philanthropist, and activist Katy Perry – I climbed all the branches of her family tree, but became enchanted with Hannah Mulhare, one of her Irish immigrant ancestors.

Perry describes herself as a “singer-songwriter masquerading as a pop star.” As one of the best-selling artists of all time (more than 100 million records to date) with sold-out world tours, she’s nailing that charade, but Hannah’s story makes it clear that Katy’s not the first in the family to pull off such a convincing deception.

Meandering Mulhares

Born in Eyrecourt, Ireland in the 1830s to Patrick Mulhare and Sarah Stanton, Anna “Hannah” Maria Mulhare was one of at least ten children. Her mother’s brother had married her father’s sister, producing a tight family cluster that was shattered when her uncle, a Ribbonman who defended the rights of tenants against absentee landlords, was convicted of sedition and transported to Australia in the 1820s. Around the time Hannah was born, her uncle was pardoned and assorted family members – including four of her oldest siblings – began drifting to Australia to join him.

The 1840s ushered in the Great Famine as well as the early days of both the Californian and Australian gold rushes, and it soon became a last-one-to-leave-Galway-turn-out-the-lights situation. While the older contingent of her siblings had opted for Australia and New Zealand, her parents and the younger ones set their sights on America.

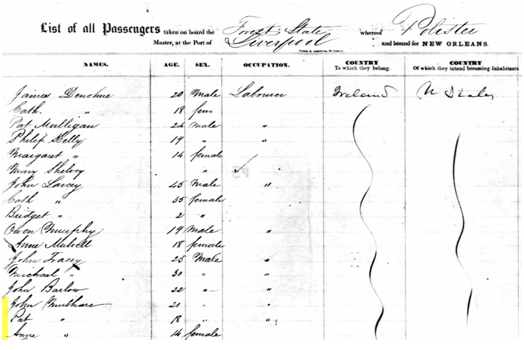

Hannah (Anne) and two of her brothers arrived in New Orleans on February 10, 1852 (Ancestry.com)

14 year-old Hannah (perhaps understated to save on fare) and her brothers John and Pat were among the 268 passengers on the Forest State when it arrived in New Orleans on February 10, 1852, but this was just a staging ground. Another brother named James had been there for some time, and made arrangements for the family to push on to California, which had only become part of America in 1848 and a state in 1850.

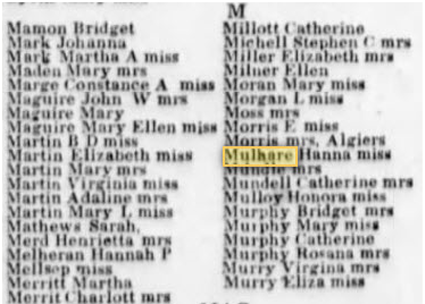

Hannah’s brief time in New Orleans left a trace when she was listed among those with letters waiting at the post office (March 7, 1852, The Daily Delta, Newspapers.com)

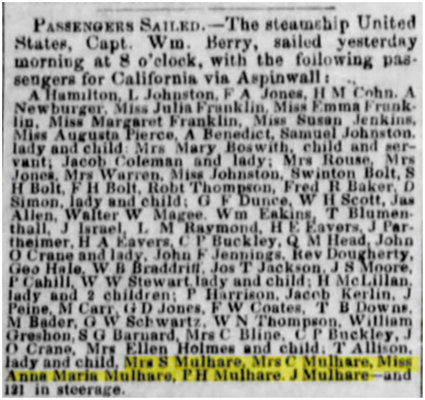

The following May, James demonstrated remarkable efficiency when he applied for a marriage license on the 2nd, became an American citizen on the 4th, and set sail on the 7th. He, his bride Catherine, Hannah, Patrick, and mother Sarah departed on the United States and headed for California via Aspinwall. Since the Panama Canal did not yet exist, this meant that they had to disembark and take a train from the Atlantic to the Pacific seaports.

The Mulhare family left New Orleans for California (May 8, 1853, The Daily Delta, Newspapers.com)

Gradually, the Mulhares, including some who had been living in Australia, reassembled in California. San Francisco became something of a hub with a rotating cast of family members based there, but other pockets settled in nearby Marin, Contra Costa, Sacramento, and Yuba counties. Those in Yuba County resided in gold mining towns whose names reflected possible outcomes of their ambitions – Smartsville and Sucker Flat.

The Mulhare patriarch, Patrick, died in San Francisco in 1858, and James – who took to using his mother’s surname of Stanton as a middle name – assumed his place at the head of the family.

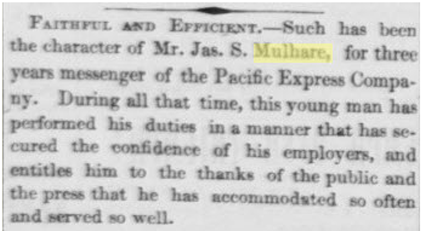

James S. Mulhare recognized for his stellar work (April 3, 1857, The Daily Alta California, California Digital Newspaper Collection)

James S. Mulhare was a prominent member of San Francisco’s Irish American community (September 22, 1858, The Daily Alta California, California Digital Newspaper Collection)

James soon made his mark with a local paper lauding his character for his work with the Pacific Express Company and recording his election as Secretary of the Sons of the Emerald Isle, established just a few years earlier. But then things took an unexpected turn.

The Old Switcheroo

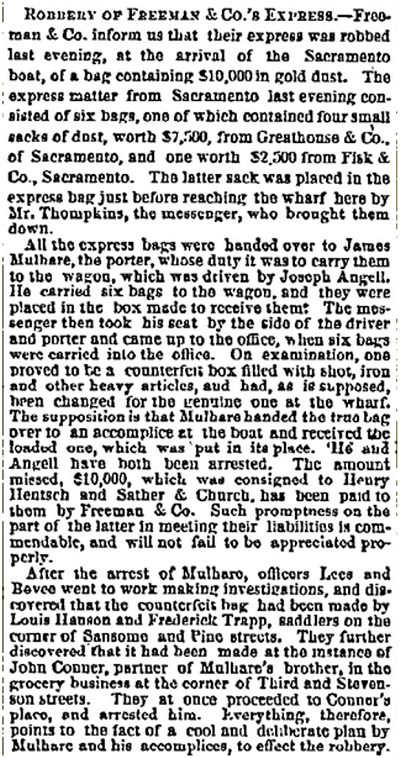

On the evening of August 1, 1859, Freeman & Co. Express Company (which would become part of Wells Fargo the next year) discovered a theft. During a delivery from Sacramento to San Francisco, a bag of gold dust worth $10,000 was swapped out with one full of shot, iron and other heavy objects. It didn’t take long to determine that the switch occurred when the consignment was transferred from the wharf to a waiting wagon, and the porter responsible was none other than James S. Mulhare.

Police failed to find the money, but a bit of clever detective work revealed that the counterfeit bag was made by a local saddler, who identified John Connor as the man who had ordered it. Connor, it turned out, was in business with another Mulhare brother and engaged to Hannah, so this was both an inside job and a family affair.

Express company robbery discovered (2 August 1859, San Francisco Bulletin, GenealogyBank)

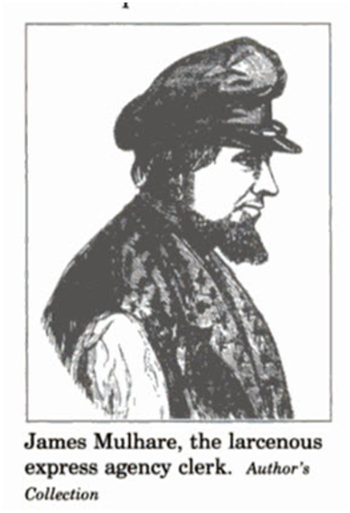

James S. Mulhare (August 27, 1859, California Police Gazette)

Mulhare and Connor were swiftly arrested, and because the attempted ruse captured the attention of the public, the story was covered not just in local newspapers, but across the country and as far away as Australia. The accused requested separate trials, and within six weeks, both were found guilty of grand larceny.

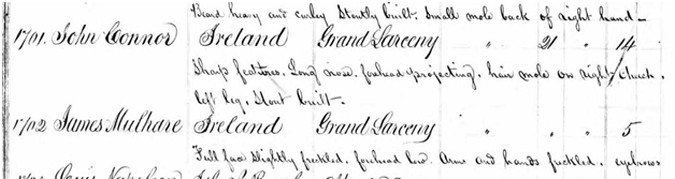

San Quentin registry entries for Connor and Mulhare (California State Archives)

Connor received a sentence of 14 years, while Mulhare – who pleaded guilty – got five. Both were sent to San Quentin State Prison where Mulhare’s entry notes a short, pale, lightly freckled man with “scant whiskers” and a scar on his right hand.

Mulhare had gone from being a pillar of the community to an incarcerated felon in the space of a couple of years and his life continued to spiral downward. In 1860, he was briefly let out of prison to attend his wife’s funeral, and six months later, lost a son.

Hannah’s Turn

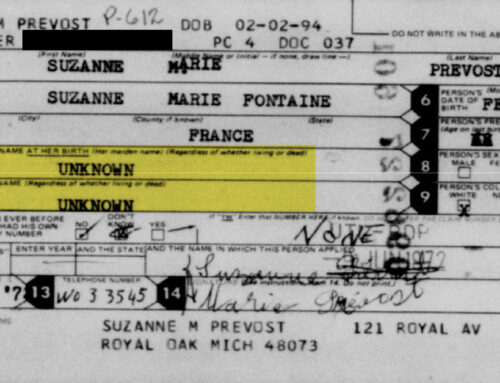

Around this same time, a fellow named James Connor – brother of the prisoner, John Connor – showed up in San Francisco and began hounding Hannah, who was working as a live-in servant for a New York physician and speculator.

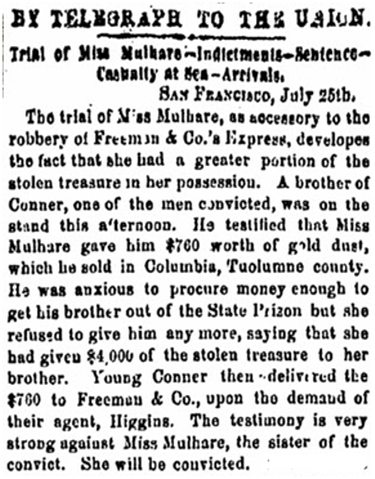

Why? During a visit to San Quentin, his brother told him that Hannah had the money, and James wanted it to try to buy a pardon for both prisoners. Hannah claimed that she only learned of the crime after the fact, and initially denied any knowledge of the money, but finally admitted to having at least some of it. James nagged her non-stop until she relented and gave him a bag of gold dust, but when converted to coin, it only amounted to $760, so he went back for the rest. Hannah dodged and promised and dodged some more, until James got fed up and went to the police.

“She will be convicted.” (July 26, 1861, Sacramento Daily Union, GenealogyBank)

The police searched her premises for the money and didn’t find any, but instead discovered the express company bag from the robbery. So it was that Hannah found herself indicted as an accomplice in July 1861.

From the testimony at her trial, it emerged that just about everyone in the Mulhare family knew about the money – at least after the crime took place – but because she was John Connor’s fiance, Hannah was the one believed to have it – though she had subsequently become engaged to another Irishman. In fact, it was her pending nuptials to another man that provoked John’s brother to go to the police.

In spite of evidence that convinced reporters that she would be convicted, her trial resulted in a hung jury, so she was scheduled for a second trial. The next round commenced in August, and on September 14th – against expectations – she was acquitted.

Hannah’s Last Laugh

Fast forward to 1864. Both John Connor and James Mulhare received pardons. Probably wishing to put his past behind him, Mulhare headed to Portland, Oregon where he remarried and began a second family before eventually returning to San Francisco.

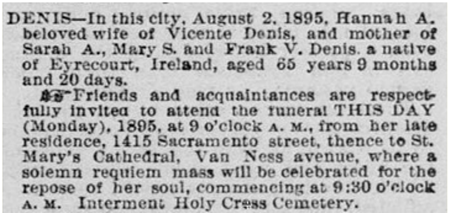

Similarly, Hannah left at least two fiances in the dust and moved to Sacramento where she married Portuguese-born Vicente Denis before circling back to San Francisco like her brother. At this point, she settled down and lived a more traditional life, raising her children, including daughter Sarah who would become Katy Perry’s great-grandmother.

Hannah’s obituary (August 5, 1895, San Francisco Call, Newspapers.com)

As to the $10,000? Accounts in the 1860s justified the pardons of Connor and Mulhare based on family responsibilites and good behavior – and Mulhare had already served most of his term. But since Connor – who still had a decade to go – received his pardon first, one can’t help but wonder if perhaps a bit of the lost money found its way to the right pockets.

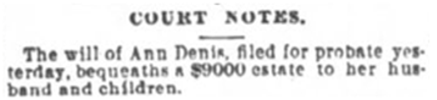

Ann “Hannah” Denis left $9,000 to her family. (August 31, 1895, San Francisco Chronicle, Newspapers.com)

And curiously, Hannah, who spent the last three decades of her life as a housewife, had the wherewithal to leave $9,000 of her own money to her husband and children when she passed away in 1895. Translated into today’s terms, that’s roughly $262,000 in spending power or $2,250,000 in economic status (i.e., relative “prestige value” of an amount of wealth).

For at least one Mulhare, it seems, chasing gold paid off.

5 Things You Didn’t Know about Katy Perry’s Roots

- Katy Perry (who uses her mother’s maiden name) is of Portuguese, Irish (about 9%), German, French, English, and Scottish origin. Through her father’s side, she has deep, mostly Southern, roots in America.

- Her mother’s family is riddled with over-achievers including philanthropists, politicians, and business pioneers in the oil, steel, banking, construction, and beer industries. Among her relatives are Charles Schwab, Leopold Vilsack, Joseph Craig, and others who were especially prominent in the history of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

- Katy’s family wasn’t the kind to let moss grow under their feet. One of her 4th great-grandmothers gave birth to five children in Alabama, six more in Kentucky, and then made it an even dozen with one more in Tennessee.

- Her Perry grandfather (grandson of Hannah Mulhare) survived the 1906 San Francisco earthquake when just a baby. His big brother recalled the city being in flames while they evacuated with all their possessions in a cart, and their house was one of many destroyed in the fire. Sadly, this family would lose their subsequent home in Mill Valley to fire as well.

- One of her great-grandmothers wrote a book called The Unpardonable Sin, which seems a likely title for a song.

Featured Photo Credit: Debby Wong / Shutterstock.com

Leave A Comment