By Megan Smolenyak

Every one of us is an amalgamation not only of all our ancestors, but of their decisions, and in 1831, Ambrose Hawkins was contemplating moving his family from America to Africa. Had he done so, his son Joseph would have been raised in Liberia instead of North Carolina and never would have become Pharrell Williams’s third great-grandfather.

As it happens, Ambrose did go to Liberia, but opted for a solo round trip, rather than a family migration. If not for this last minute change of plans, the gene pool that would eventually produce Pharrell couldn’t have crystallized. He wouldn’t exist and the rest of us would be considerably less Happy. We wouldn’t Get Lucky and those Blurred Lines would remain clearly demarcated. All because one man changed his mind 183 years ago.

The Phenomenon of Pharrell

If you didn’t know who Pharrell Williams was last year, you certainly know now. Long a major player in the music and fashion industries, his public profile exploded when we all started noticing the fellow with the park ranger hat (@Pharrellhat boasts more than 20,000 followers on Twitter) showing up at every awards ceremony as both a performer and recipient. Around the same time, Happy became a worldwide sensation sending people from Poland to Cambodia into spasms of gleeful, unfettered, YouTube-shared dancing.

It didn’t take long to realize that Pharrell was the secret sauce behind countless hits (Snoop Dogg’s Drop It Like It’s Hot, Britney Spears’s I’m a Slave 4 U, Gwen Stefani’s Hollaback Girl, etc.), a musical collaborator with the likes of Jay-Z, Daft Punk, Miley Cyrus, Justin Timberlake, Ludacris, and Robin Thicke, and a multi-faceted entrepreneur and artist with business interests ranging from his Billionaire Boys Club clothing brand to jewelry, furniture, sculpture and furniture design partnerships with everyone from Louis Vuitton to Takashi Murakam. And, oh yeah, he was once voted “Best Dressed Man in the World” by Esquire.

Pharrell’s Family Tree

A Virginia Beach native and adopted favorite son of Miami, the cultural icon has one son named Rocket with his wife, Helen Lasichanh, but what about the family tree that produced him? I was curious, so decided to investigate.

Rarely have I researched a family that was so geographically concentrated. Generations of his forebears have called Virginia and North Carolina home. Virginia Beach and Norfolk feature prominently, as do Nash, Halifax, Johnston and Currituck counties in North Carolina. His tree is populated primarily by common surnames – Williams, Johnson, Allen, Edwards and Cooper among them – but also peppered with intriguing first names such as Cain, China, Fenner, General, Hilliard, and my favorite, Napoleon Bonaparte, known to his friends as “Bone.” But of all those ancestors, it was Ambrose Hawkins who caught my attention.

Why Ambrose?

Ambrose Hawkins was born about 170 years before Pharrell and was just one of his 64 fourth great-grandparents, so why obsess on him? On the surface, his life was ordinary enough. Born in Halifax County, North Carolina, he lived there all of his life. He married as a young man of 20 or so and had at least five children with his first wife before she passed away, prompting him to marry a second time.

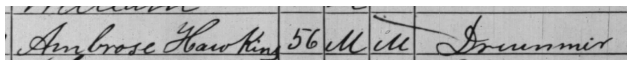

(1860 Federal Census entry for Ambrose Hawkins (National Archives and Records Administration)

(1860 Federal Census entry for Ambrose Hawkins (National Archives and Records Administration)Like many other family members, he worked as a shoemaker, though it brought a smile to my face when I noticed that the 1860 census recorded his occupation as drummer. As one who believes that non-physical traits are also passed down through the generations, I thought I had stumbled on to a scrap of evidence that Pharrell was not the first in his family to be musically inclined, but then it dawned on me that Ambrose was likely a shoe drummer, the term once used for representatives of footwear manufacturers. A heartbeat later, I flashed back to the Swarovski crystal-encrusted Adidas Pharrell wore on SNL, Good Morning America, and Ellen, and realized that his roots were claiming him after all.

A Free Person of Color

Fellow history buffs will understand that it was the very fact that Ambrose appeared in the 1860 census that made me do a double take because this told me that he was free before Emancipation. He was, in the parlance of the day, a “free person of color.” Had he been enslaved, he would have been reduced to a nameless entry of gender, age and race (typically, black or mulatto) on the slave schedule of his owner – a genealogical reality that robs descendants of critical clues for uncovering the lives of these relatives. But Ambrose and his family members, like roughly ten percent of African Americans at the time, were free before the Civil War and that meant there would be more of a paper trail to follow.

I began meandering back through the decades taking care not to confuse Pharrell’s ancestor with two white men also named Ambrose Hawkins living in the same vicinity. Fortunately, they were fairly easy to sort out due to age differences. It was clear that Ambrose was well regarded in the community as obtaining a gun license in the 1840s required a petition signed by five or more “respectable neighbors,” a qualification he was able to meet.

I kept working my way back and was able to find him as early as the 1830 census, indicating that he was free by that time. In fact, the more I dug, the more reason I found to believe that his family had been free for some time – well into the 1700s. Regrettably, I was unable to find documents that could explain how or when the Hawkinses secured their freedom, but at least one branch of the family claims Native heritage. While many more people think they have Native ancestry than actually do (DNA testing has shown this to be the case), this possibility offers a plausible theory. Several years ago, I researched the family tree of Michelle Obama, the largest portion of which also straddled the Virginia-North Carolina border (in her case, further west than Pharrell’s family). In that instance, a circa-1800 court case involving a woman who obtained her freedom based on Native descent shed light on one of the First Lady’s lines, but if such records exist for Pharrell’s family, they have yet to be discovered.

An African Connection

Since this goal eluded me, I focused on finding out whatever I could about Ambrose Hawkins and that’s when I first learned of a possible connection to Africa. Taking advantage of his somewhat unusual name, I tried googling it in conjunction with a variety of other relevant words, and tripped across several mentions from The African Repository and Colonial Journal of the American Colonization Society (ACS).

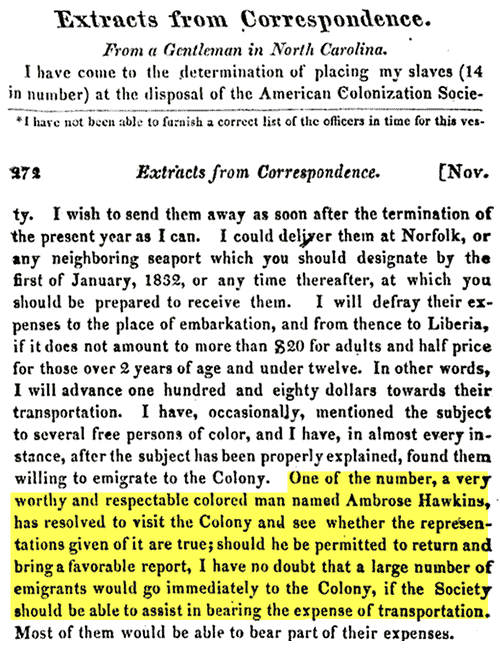

I wasn’t entirely sure it was him, but the first reference was excerpted from a letter written by a “gentleman in North Carolina,” apparently in 1831. The correspondent, whose name was not included, described Ambrose as “a very worthy and respectable colored man,” so it seemed likely since the two white, North Carolina-based Ambrose Hawkinses could be ruled out.

Frankly, I wanted it to be him as the letter described a curious proposition: Ambrose Hawkins wished to visit the colony to see things for himself, but didn’t intend to stay. “Should he be permitted to return and bring a favorable report,” the writer continued, “I have no doubt that a large number of emigrants would go immediately to the Colony.”

I was familiar enough with the American Colonization Society and its role in the founding of the country of Liberia to realize that the colony in question was in West Africa. So rather astonishingly, Ambrose, a free man of color, was essentially campaigning to take a 9,200 mile round trip to Africa in 1831. Moreover, he was a man of influence whose opinion was valued by others – enough that they would consider emigrating based on his word.

I thought that identifying the letter-writer might offer confirmation that this Ambrose was indeed Pharrell’s ancestor, so burrowed deeper. Further exploration of the online ACS’s journal turned up a single entry that looked promising: “Joseph R. Gray, of Halifax Co., NC liberates 14.” Since the opening line of the correspondence that mentioned Ambrose read, “I have come to the determination of placing my slaves (14 in number) at the disposal of the American Colonization Society,” it seemed that this was probably the right man.

A quick search of the 1830 census turned up a Joseph J. Gray who lived very close to Pharrell’s fourth great-grandfather – just four census pages away. The same record indicated that he owned 14 slaves. Everything but the middle initial matched, so I was confident that this was the “gentleman from North Carolina” and the right Ambrose.

Having learned that the Society’s original records were housed at the Library of Congress, I decided to go look for myself. A finding aid informed me that ACS records for this timeframe were voluminous, but roughly chronological and now I knew whose letters to look for. My hope? Maybe there would be other mentions of Ambrose or even a letter or two from him. But first, I needed to refresh my memory on the American Colonization Society.

Ambrose Hawkins mentioned in a letter sent to the American Colonization Society (Google Books)

Ambrose Hawkins mentioned in a letter sent to the American Colonization Society (Google Books)

American Colonization Society

With apologies in advance for this over-simplification, the American Colonization Society was created in 1816 with the objective of transporting free blacks from America to a colony in Africa. Paul Cuffee, a New England sea captain of African and Native heritage, piloted the idea in 1815 by taking 38 individuals to Sierra Leone, but passed away before getting much further – though not before inspiring others. Among the founders and early members of the ACS were notables of the time including Henry Clay, Francis Scott Key, Daniel Webster, Andrew Jackson, and Bushrod Washington, the Society’s first president, a Supreme Court Justice, and nephew of George Washington.

Sponsoring the first emigrants in 1820, the ACS would ultimately be instrumental in sending thousands of Americans to Africa, as well as in the establishment of Liberia (Descendants of the earliest emigrants would run the country for over 130 years from the time of its official founding in 1847.). The organization dwindled in the early-1900s, but wasn’t formally dissolved until 1964. It was controversial from inception and remains so today with academic consensus shifting over time, not surprising given the mixed bag of motivations behind the Society and among its supporters and members.

Some abolitionists, for instance, believed that blacks would never have equal opportunities in America, so would be better off in Africa. But these benevolent intentions were countered by those who regarded blacks as inferior and a burden to society. Still others perceived free blacks as a threat because they might undercut wages, or worse, incite slaves to revolt. So it was that a peculiar coalition, encompassing everyone from Quakers to slaveholders, formed. While they held widely divergent views, they found common purpose in “repatriation.” The solution, they felt, was to “re-convey them to the land of their fathers” – “them” being free persons of color.

In language and logic that makes us wince today, the Society argued, “If we received them slaves, return them freemen. If they came hither Pagans, let them go back Christians – bearing with them the example and the fruits of civilized life, and the still more inestimable tidings of salvation, to the hordes of Africa.” This approach would relieve “the South from danger, and the North from pauperism.”

These quotes, complete with their deliberately italicized words, come from a letter written on December 10, 1831 by W.A. Duer, President of the New York chapter of the Society, as well as President of Columbia University. That same day, Pharrell’s ancestor, Ambrose Hawkins, was on a ship headed to Liberia.

Liberia Bound

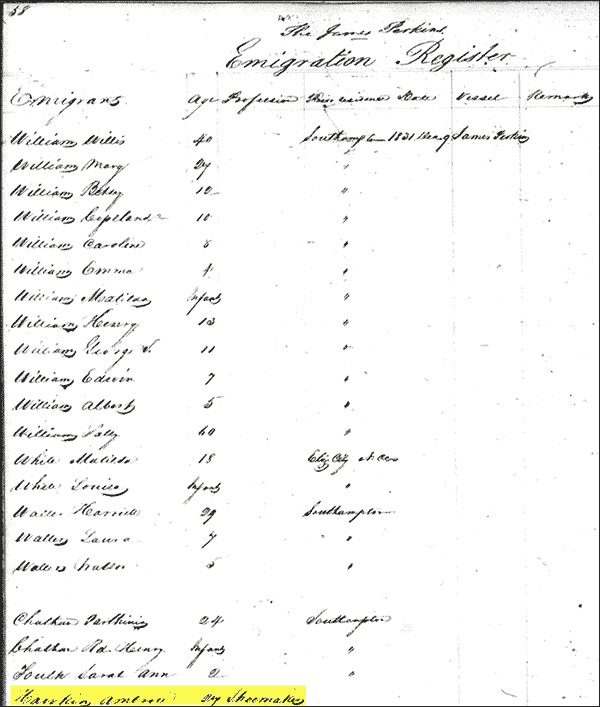

I know this because before even before I went to the Library of Congress, I searched the Virginia Emigrants to Liberia website (www.vcdh.virginia.edu/liberia), the engaging brainchild of historians Marie Tyler-McGraw, Deborah A. Lee, and Scot French. Though he wasn’t from Virginia, Ambrose Hawkins is included in this emigrants database. Looking later at a copy of the original document, I saw that he was recorded immediately after three others from Southampton, Virginia. There were no ditto marks next to his name, and since there was no place of origin at all listed for him, the natural assumption would have been Southampton – especially given that the vast majority of those on board were from Virginia and more than 80 percent from Southampton.

Ambrose Hawkins, age 27, shoemaker on emigration register for The James Perkins

Ambrose Hawkins, age 27, shoemaker on emigration register for The James Perkins

(Reel 314, American Colonization Society Records, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.)

The ship was the James Perkins and the manifest notes that it left Norfolk on December 9, 1831. This corroborated another ACS letter I found online from an enthusiastic emigrant named Robert Allen, a ship carpenter and preacher. Dated January 23, 1832 from Monrovia (they had arrived on the 14th after five weeks at sea), he wrote of the “delightful passage,” his favorable impressions of the colony, and of receiving “attention and kindness from Mr. Ambrose Hawkins, quite a genteel young man.”

As it happened, Robert Allen was the first person listed on the manifest and Ambrose Hawkins the last. This trip by the James Perkins would carry 338 passengers, the largest ever, single influx of emigrants to West Africa, and along with a cluster of other ships (Elizabeth, Nautilus, Oswego, Cyrus, Vine, Indian Chief, Doris, and Harriet) would become part of the pioneer lore of Liberia.

I would later discover how lucky I was that the manifest still existed. The original had been stolen in a case that had been left momentarily unguarded in Norfolk, but due to departure delays caused by suspected overloading and weather issues, the shipping agent had time to draw up a new passenger list. Had that not been so, this proof of Ambrose’s extraordinary journey may well have evaporated.

The Middleman: Joseph J. Gray

At this point, I treated myself to a two-day immersion at the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress, a genealogist’s version of vacation. My sister, who’s usually game to accompany me on my random deep dives into history, came along to help. Two sets of eyes proved to be very useful for the task before us.

We quickly developed an efficient process for scanning the semi-organized files of the Society, plucking out and copying the relevant bits. As I had hoped, Ambrose was mentioned in more letters, though we weren’t fortunate enough to find anything written by him. But Joseph J. Gray had exchanged at least seven letters with ACS, four of which discussed Ambrose. The remaining letters concerned 14 slaves he would send on a later ship in May 1832, various donations, and other matters. We also pored over emigrant lists, interoffice mail, board minutes, and other materials to get a more complete picture.

Armed with a flash drive full of digitized documents, I returned home to digest these papers, but found myself curious about Joseph J. Gray, so took a detour to look further into him. What emerged was the impression of a man evolving, becoming zealous in pursuit of a cause, and eventually running out of steam.

Born into to a well-to-do family, but orphaned at a young age, he experienced a religious awakening at college. Joseph studied first in Raleigh, North Carolina and later at Union College in Schenectady, New York, where his theological interests deepened.

“Joseph J. Gray’s home just south of Brinkleyville, North Carolina

“Joseph J. Gray’s home just south of Brinkleyville, North Carolina(http://www.hpo.ncdcr.gov/nr/HX0019.pdf)

In the 1820s, he built a home in Halifax County that still stands today and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places as the Gray-Brownlow-Willcox House. This would have been the place he brought his first wife, a niece of Union College’s president, Eliphalet Nott, to in 1826. The 1830 census finds him living there in a household of 21, including 14 slaves.

Then in rapid succession, he corresponded with the ACS about his desire to liberate his slaves and arrange for them to emigrate to Liberia, encouraged the Society to send Ambrose Hawkins and later Rev. John Nott (an apparent relative of his wife’s) to travel to Liberia so they could return to essentially help “market” the initiative, became a Presbyterian minister, released his slaves for “repatriation,” sold his home, and moved – initially elsewhere in North Carolina, and later to Indiana and Illinois. Due to health issues, his ministerial career was brief, and like many at that time, he remarried upon losing his first wife. His post-1840 life was unremarkable and he would eventually die an elderly man in Macoupin County, Illinois in 1888.

Over the course of Joseph’s exchange with the Society, he became increasingly zealous, using flowery language in praise of its “noble cause” and hailing “with joy every occurrence which has even the remotest bearing on the prosperity of your excellent institution.” His effort to have the ACS sponsor a round trip for Rev. Nott was seemingly an attempt to engage the backing of the Presbyterian Church. He assured the Society that, “friends would be raised up, prejudices removed, correct information diffused, and the pecuniary interests of the colony greatly promoted.” His powers of persuasion convinced the board who approved the journey, but no record can be found of Rev. Nott ever going.

Joseph’s ardent belief in the objectives of the ACS is evident, but just as his fervor reached a peak, it abruptly faded. Perhaps it was his ordination as a minister that distracted him, or his pending move, or his growing frustration trying to get others to see what was apparently so clear to him, but whatever the cause, his later letters were brief and business-like.

A Change of Heart

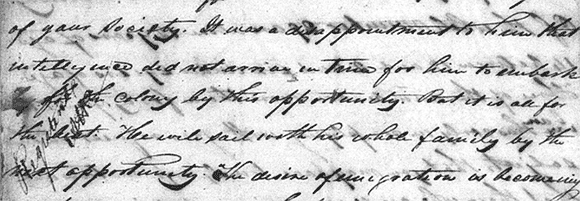

Having located additional materials mentioning Ambrose Hawkins, I was able to get a fuller understanding of his story which was slightly more complicated than I had first thought. After Joseph’s initial request, the board agreed that, “Ambrose Hawkins may have a passage in the Margaret Mercer now to sail from Baltimore to return in the first vessel of the Society returning from the Colony,” but it seems that a couple of letters were lost or at least delayed in the mail.

By the time Joseph and Ambrose learned of this, it was too late to get to Baltimore for the departure, but in his next letter, Joseph presented this as a positive development, saying, “It was a disappointment to him that intelligence did not arrive in time for him to embark for the colony by this opportunity. But it is all for the best. He will sail with his whole family by the next opportunity.”

Excerpt from letter from Joseph J. Gray to ACS, September 29, 1831

Excerpt from letter from Joseph J. Gray to ACS, September 29, 1831(Reel 12, American Colonization Society Records, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.)

So after pondering, Ambrose had decided to take his family with him. His intention had shifted from checking Liberia out to emigrating. This was a surprise. What had changed his mind? Joseph’s next letter answered that question:

“Since Hawkins could not embark on the Margaret, he has determined to sail with his whole family at the time specified in your letter. It is the prerogative alone of the Almighty to bring good out of evil. The tragedy acted lately in Southampton, VA was truly shocking to every feeling of humanity, but I have no doubt it will be overruled for the wisest and most benevolent of purposes. I think I can very plainly discern already some beneficial aspect both on the white and free colored population. It has caused many white men to think about the nature and the consequences of slavery who would in all probability never have thought about the subject at all. It has evidently opened the eyes of many of the free colored population to their true situation. It has taught them that they have the shadow without the substance of freedom, the name without the privileges of free men.”

Nat Turner’s Rebellion

Southampton, 1831. Of course. Nat Turner’s Rebellion. In August 1831, Nat Turner started an insurrection that involved mostly enslaved, but also some free blacks. While figures vary, most agree that at least 55 white people were massacred in Southampton County in just a couple of days. Turner escaped and managed to evade capture for two months, but was finally caught on October 31st. Swiftly tried and sentenced to death, he was hanged on November 11th.

Nat Turner’s rebellion tapped into every slave-owner’s worst nightmare and the resulting backlash was fierce. As Marie Tyler-McGraw so aptly put it in An African Republic: Black and White Virginians in the Making of Liberia, the outcome was a “reverse bloodbath for African Americans in the region.” The James Perkins that Ambrose sailed on in December was the first ship to depart for Liberia after the revolt and its aftermath, which explains why he had so many fellow travelers and why so many of them were from Southampton.

Halifax County, North Carolina was only about 70 miles from Southampton and the hysteria had already spread there by the time the rebellion was being quelled. One newspaper printed a letter from Halifax County dated August 24th that stated, “I want you to send me per first boat 2 kegs gun powder. The negroes have risen against the white people, and the whole country is in an uproar. We have to keep guard night and day. We have had no battle yet, but it is expected every hour.”

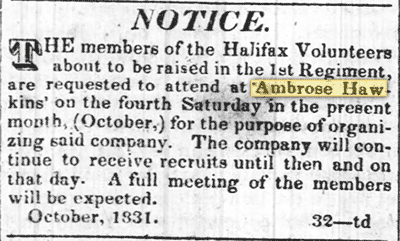

Shortly thereafter, it was reported that these claims were “without foundation,” but the failure to find Nat Turner kept fear alive. Just days before he was captured, a session to organize the 1st Regiment of the Halifax Volunteers was called. The meeting place? The property of the elder, white Ambrose Hawkins.

27 October 1831, Roanoke Advocate (as seen on Newspapers.com)

27 October 1831, Roanoke Advocate (as seen on Newspapers.com)

Before this rebellion, the American Colonization Society had a hard time selling its emigration scheme to free blacks. Why move to a continent you had never been to? Why shouldn’t you be able to live in peace and freedom in the country of your birth? For many, the violent repercussions of this revolt altered the equation.

Ambrose’s Decisions

Ambrose Hawkins hailed from a family that had been free for generations, and he was personally respected in his community, so it’s easy to understand why he would have expressed skepticism or disinterest when first approached by Joseph. And it’s just as easy to see what made him reconsider. History and reputation meant nothing in the reprisals. Free people of color were targets, and if Ambrose needed any evidence, a militia was being raised by his namesake. Under the circumstances, leaving probably seemed the prudent thing to do.

Still, the journey was not without risk. In one of his letters penned while Ambrose was at sea, Joseph wrote, “Ambrose Hawkins obtained a passage to the James Perkins for the colony with the intention of returning again if his life should be spared.” Disease and disputes with native Africans who didn’t appreciate the sudden appearance of “repatriates” had taken a heavy toll on early emigrants. Ambrose knew even going there involved some danger, and whether for this reason or due to logistical issues (perhaps he was concerned that the board would rescind its offer if he did not go on the next ship), he went alone in December, rather than with his family.

Unfortunately, the official record is silent on Ambrose’s opinions regarding Liberia, but we can gather that he liked what he saw by events of 1832. He arrived in Liberia on January 14th, and presumably departed with Captain Crowell on January 26th, meaning he had a dozen days to form an impression. He would have arrived back in America in late February or perhaps early March, and in May, Joseph sent his 14 emancipated slaves to Liberia.

Joseph and Ambrose liked and admired each other. Joseph’s comments on Ambrose in his letters make his perspective clear and the fact that Ambrose named a son born around this time Joseph J. – the one who would go on to become the third great-grandfather of Pharrell Williams – suggests that the feeling was mutual. It’s highly unlikely that Joseph would have sent his slaves to Liberia if Ambrose had come back alarmed or dissatisfied. More to the point, Ambrose sent some of his own family to Liberia.

Grays and Harwells

The manifest for The Jupiter that left in May of 1832 contains a cluster of Gray relatives from Halifax County and notes that they were liberated by Joseph J. Gray. On the next page are eight free-born Harwell family members, also from Halifax County. About a decade earlier, Ambrose had married China Harwell, and these passengers were a collection of his in-laws and nieces and nephews.

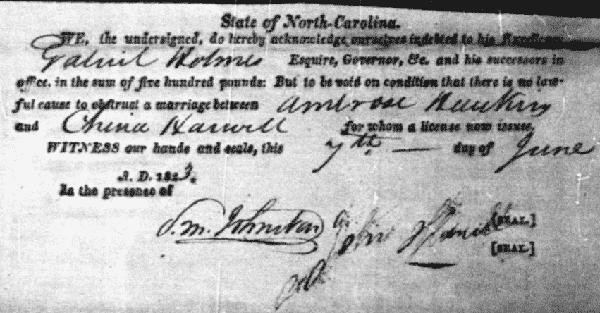

1823 Marriage of Ambrose Hawkins and China Harwell

1823 Marriage of Ambrose Hawkins and China Harwell“North Carolina, County Marriages, 1762-1979,” index and images, FamilySearch

(https://familysearch.org/pal:/MM9.3.1/TH-266-11931-82111-21?cc=17269574), 004364158 > image 1881

Traces of the Gray family members can be found in later years. Dublin Gray would double back to the U.S. in 1834 to bring still more Gray relatives to Liberia. That same year, Brazil Gray would be accused of “going native” and marrying multiple, local women, a claim disputed by others. And members of their families can be found in a colonial census conducted in 1843.

Regrettably, the same cannot be said for Pharrell’s relatives, the Harwells. David Harwell succumbed to disease in 1835, but few traces are found of the others, though there are hints of a merging with a White family. John W., Mary and Kitteral Harwell, for example, are elsewhere recorded as John, Mary and Kitro White, and an 11-year-old in the 1843 census is named Harwell White. My best assessment would be that the other adult male Harwell who made the crossing, Nat, died and his widow remarried (likely to a Richard White) causing the Harwell and White names to cross-pollinate in various ways. Assuming Nat’s children survived, they probably adopted the White name.

What If?

Motivated by threatening events and urged by Joseph Gray, Ambrose Hawkins made the bold decision to go to Liberia in 1831 and ventured on a round trip ocean crossing at a time when this was a risky, multi-month affair. He saw this as the way forward for his family, and was pleased enough with what he encountered in Liberia to encourage his wife’s relatives to make the move and to support Joseph’s plans to liberate and send his slaves there. But for reasons we’ll probably never know, he didn’t return.

Perhaps he had second thoughts after things settled down post-rebellion. Maybe Joseph’s departure from the area dampened his enthusiasm and made communicating with the ACS more difficult. Or maybe the Harwells did not fare well. Many emigrants wrote home, so it’s possible he would have learned of their hardships and changed his mind. Whatever the reasons, we are all the beneficiaries today.

As I researched this tale, peeling back layer after layer, I found myself playing the “what if?” game. I recalled a meeting I had in Slovakia with distant cousins whose great-grandfather had emigrated to America, but like many at the time, returned home to be the richest man in the village thanks to the earnings he had acquired overseas. After chatting with them, I reflected on how different my life would have been if my own great-grandfather had gone back to the old country, starting with the fact that I would have been raised under Communism. But then I realized how hyper-hypothetical my musings were because the simple truth is that if he had, I would not exist. The Slavic and Irish sides of my family tree never would have collided, and for that matter, my father wouldn’t exist either. Pharrell’s family saga was a different spin on the same story, and most of us have some variation of this theme in our family history.

One of my favorite aspects of genealogy is that it helps us grasp in an almost tangible way how interconnected we all are and opens our eyes to the impact each of us has on others. Whether he knows it or not, Pharrell Williams has a connection to and probably some cousins in Liberia. Think your decisions don’t matter? Especially if you have or plan to have children, think again. The choices you make today can ripple down through the generations. Because of a change of heart Ambrose Hawkins had in 1832, Pharrell Williams exists and the whole world’s doing a Happy dance.

© 2014 Megan Smolenyak

Additional Articles by Megan

“Megan, I truly appreciate what you’ve done for me.

My Mom would be so very proud. Love ya! — Joe Biden”

Irish America Magazine

“Joey From Scranton

Vice President Biden’s Irish Roots”

by Megan Smolenyak

[See pages 56 – 59]