A bunch of people named Smolenyak, all hailing from the same tiny village, thought they shared a common ancestor. We were wrong.

Road to nearby village of Ždiar from Osturňa in 2000 (photo by husband of writer)

Many are not aware that genetic genealogy has been around for slightly more than two decades. I was introduced to using DNA for forensic purposes back in the dark ages of 1999 when I began my work with the U.S. Army assisting with the identification of soldiers still unaccounted for from conflicts ranging from WWI to Vietnam. As a result, I was an early adopter when the first commercial testing companies launched in 2000, but as often happens with new technology, there was a lot of resistance in the early days.

In spite of already being an established writer and speaker, as the first professional genealogist to be a proponent for genetic genealogy, it took me two full years to get anyone to accept an article or talk on the topic. This article, the first one I managed to get published, had been turned down by all the other genealogical magazines. “Everton’s Genealogical Helper” ran it in their May/June 2002 issue. I share it today to provide some insight into how much has changed – and how much hasn’t.

Our History Mystery

Smolenyak is a genealogically convenient name. There aren’t all that many of us, and although we are now scattered from Ukraine to Antarctica, years of research have revealed that we all trace our roots to the same geographically isolated village of Osturňa, Slovakia. As if that weren’t tidy enough, the records of St. Michael’s Greek Catholic Church, the only church in the village, show that the Smolenyaks lived decade after decade in the same four households: numbers 88, 96, 103, and 135.

Following the paper trail of church, land, and census records, we were able to track these households as far back as the 1740s. As we worked our way back from generation to generation, we kept looking for hints of the four households converging. Surely such a secluded cluster living in such close proximity to each other must have common roots, we reasoned. When 1715 military conscription records contained only a single draft-eligible Smolenyak, we became even more convinced that we had a common ancestor, though not necessarily this particular fellow.

But now the trail was cold. While we still hope for the discovery of new Osturňa records, we knew not to be overly optimistic since the church was burned in 1796. Keeping our genealogically convenient pattern intact, members of each of the four Smolenyak households had emigrated to the United States between 1890 and 1909, and their descendants were all very curious to know if we were, in fact, distant cousins. How were we ever going to solve this personal history mystery?

DNA Testing to the Rescue

Fortunately for us, we reached this impasse just about the time DNA testing first became available to everyday consumers, willing to part with $200-300 per test. Our situation presented the perfect surname or Y chromosome case study. The Y chromosome is passed from father to son down through the generations. Tracing the chromosome is essentially the equivalent of tracing the history of one’s surname along the top line of a pedigree chart. This type of testing is frequently used in genealogy to determine whether scattered individuals with the same surname share a common ancestor, and that was exactly how we planned to use it.

We would simply have to get samples from each of the four Smolenyak lines. If they matched, we would have proven our theory that we all had a common ancestor. If only some of them matched, we would at least know in advance which lines would converge and where to focus our future research efforts. And if none of them matched? Well, that was just silly. Not even worth contemplating.

With the help of a few generous sponsors within our Osturňa Family Association, we arranged to work with Family Tree DNA of Houston, Texas. At the time we began, they were offering testing with 12 markers to help ascertain matches. Family Tree DNA and Ancestry. com now offer 21 and 23-marker tests, respectively; 12 was the most available from any commercial service at the time, making their results more reliable than others (Note: This is an example of one aspect that has changed considerably since 2002!).

We were also attracted by the fact the Family Tree DNA maintained a database of samples over time and would notify us of any matches now or in the future. Even before we launched the Smolenyak-specific inquiry, we already had plans to extend the study to the entire village, so this ability to gradually build an Osturňa database that could potentially reveal new links and other surprises that documents could not appealed to us.

Now it was just a matter of convincing men from each of the four lines to participate in the mouth swab test. We anticipated some objections, and questions about privacy matters, but due to our long-established village association and the resulting trust and relationships built over the years, everyone asked obligingly provided a sample.

Americans of Osturňa descent during second trans-Atlantic reunion there (2000)

The Envelope, Please

Samples from each of the four Smolenyak lines were submitted for testing, and we impatiently counted down seven weeks for the results. Finally, the wait was over.

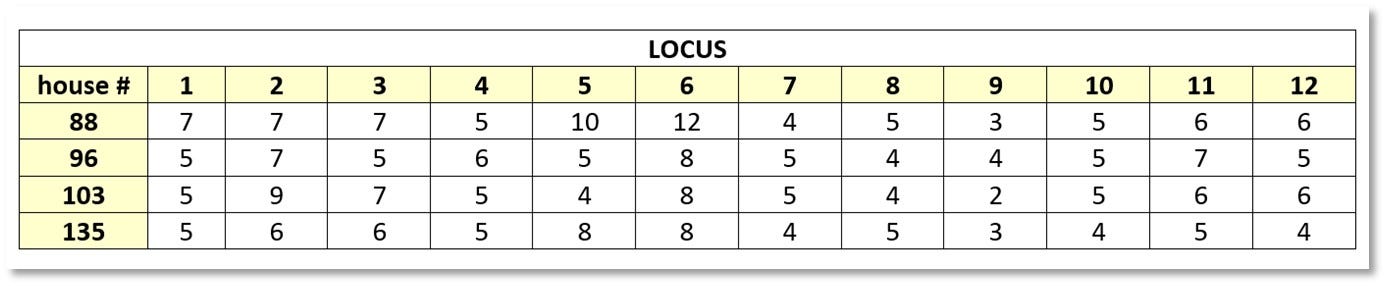

We tore open the envelopes with the test results, and against all our expectations, none of the samples matched. In fact, none of them even came close! This can be seen by comparing all the marker for the four samples (see table). In order for any two of the lines represented to share a common ancestor, one would expect to see a minimum of ten of the 12 matching, and even that could have left us second-guessing the results.

A locus is a location on the chromosome. Each locus has alleles, or identification markers. The testing used for this study included 12 such markers which are shown for each of the four Smolenyak households.

While waiting for the preliminary round of results, we had submitted another pair of Smolenyak samples, one each from houses 88 and 96. These came back as perfect 12 for 12 matches with the other samples from their respective households, so the accuracy of the testing was beyond doubt.

There was no escaping what the testing was telling us: each of the four Smolenyak lines stems from a distinct ancestor.

We know that this does not mean that there is no relationship between these four lines at all. For instance, from our earlier research, we know that there is a blood tie between houses 88 and 96 around the mid-1700s, but it is through a collateral (i.e., non-Smolenyak) branch of the family trees. Still, we were stunned to learn that our long-cherished perception that we were all kin had been disproved. As we pondered our sudden unlinking, several theories emerged that could possible explain these unexpected results.

Unknown Father Theory

One possibility is that there had been one or more mystery fathers in our Smolenyak lines. Since the Y chromosome is passed from father to son, any time a man’s wife has been unfaithful and passed off another man’s son as her husband’s, the Y chromosome chain is broken. While this is presumably a rare event, one has to consider that just one such event in the hundreds of years the Smolenyak name has existed could break the chain in any of the lines. In other words, a father who was deceived back in the 1700s would affect our results today.

Similarly, a surname passed from mother to son (say, in the case of an illegitimate birth) would result in a child bearing a surname that does not reflect his Y chromosome heritage. All his descendants would then share this genetic “mismatch.”

Surname Origin Theory

Another theory assumes that the results are completely accurate and reflect how surnames were developed in Osturňa. “Smola” means pitch or tar in most Slavic languages, suggesting that the first men given this surname perhaps worked with pitch or tar (roofers, for instance). Given that a number of Osturňa surnames are descriptive (translating to bald, toothless, etc.), it could also have been a nickname of some sort. In either case, one could easily imagine that at the time surnames were handed out in Osturňa (we believe around the 1600s) that two or more men could have fit the Smolenyak category even though they had no relationship to each other. If this were the case, our families may have been completely different ones that accidentally wound up with the same, rather unique surname due to a similar appearance or occupation.

Surname Evolution Theory

Blended families frequently resulted in surname confusion and modification over time. Because of early deaths of spouses, many of our ancestors had multiple marriages. In such cases, one often finds households with children that are his, hers, and theirs. Over time many of the children from such unions in Osturňa had a tendency to casually bounce back and forth between the surnames of their birth father and stepfather. If the surname that finally “stuck” and was passed on to descendants was actually the stepfather’s, there is once again a genetic mismatch.

A naming quirk in Osturňa may have also exacerbated this kind of surname confusion. When there came to be too may people of a particular surname, the name would often be modified by a descriptor. For instance, if there were too many Smolenyaks, a particular family may have been referred to as the “Mudrak Smolenyaks” (perhaps this was the wife’s maiden name) to distinguish them from others. Over time, this qualifier sometimes developed into the actual surname. Yet again, a genetic mismatch between surname and Y chromosome heritage would be created.

What Next?

We could have simply declared that the surname origin theory was probably true – that several unrelated men were given the same surname when they were first parceled out – and just have left it at that. But we’re not quite content to do that when we can still pursue the other theories. For instance, there is an apparent blended family situation around 1800 concerning household 103 and the surname of Vanecsko. By tracing some of the Vanecsko lines into the present and having them tested, we may be able to ascertain the house 103 Smolenyaks are really Vanecskos by origin (Update: We did so and this turned out to be the case). Similarly, we have a centuries old illegitimate child situation (in which we can make an educated guess about the father) that we can try testing for one of the households.

But our best hope for learning more may be our village wide study. While this is admittedly a somewhat blind approach, we have asked others with Osturňa origins to volunteer for testing. We speculated that because our ancestors were so isolated for so long, there might be something of a village pattern, and that even if that weren’t the case, we would likely find some unexpected connections or possibly clues to our pre-Osturňa origins.

To date, only five of the approximately 50 Osturňa surnames have been tested, but we have already had two surprising results. One of the other surnames, Bizub, turned out to be ten for 12 match with one of the Smolenyak households. Since the two markers that did not match were only off by one, we believe they may share a common ancestor, albeit many generations ago. The other surprise is that one of our seemingly Greek Catholic families may actually have Jewish origins. Additional testing is being performed to pursue this interesting possibility.

We intend to continue our specific theory testing in conjunction with our less-directed village testing. Each set of result provides us a little more data to interpret and we are quickly learning to expect the unexpected. In this manner, we hope to inch toward a better understanding of our Osturňa roots, and we feel that in some small way, we are genetic genealogy pioneers (Update: National Geographic’s Genographic Project wasn’t launched until 2005, so we were definitely ahead of the curve in terms of place-centered research!).

Osturňa-based painting of writer and family members by her step-father

A Step Closer to the Truth

We all know that in traditional genealogical research, you have to be prepared for what you might find. The same holds true when you apply DNA testing to family history research. If four clusters of Smolenyaks who knew in advance that they hailed from within a 50-house distance in a tiny, off-the-beaten-path village don’t have a common ancestor, how many others are out there making false assumptions just because ancestors of the same surname hail from the same village? Fortunately, we now have this tool of DNA testing to assist in our roots-quest, and many surname studies have already been conducted or are underway for a wide variety of names. Some of those being tested are bound to find themselves as perplexed or disappointed by their results as we initially were, although I suppose the fact that I happen to be a Smolenyak who recently married a Smolenyak from one of the other lines gives me reason to sigh with relief? From the paper trail, we already knew that any blood connection between us was centuries old, but I confess that my husband and I were perhaps a little less disappointed than the others to learn that none of our Smolenyak lines ever connect.

Even without this quirky family situation, though, I am relieved to have not spent my whole life believing a genealogical myth of a common ancestor who didn’t exist. My thoughts now turn to how we can creatively use this new-found knowledge, all the hours we will save by not trying to prove a false connection, and both traditional and DNA research techniques to find the real truth of our origins. I hope you’ll excuse me, but I need to go campaign for a few more mouth swab samples!

DNA testing done in Osturňa by writer in 2004

Leave A Comment