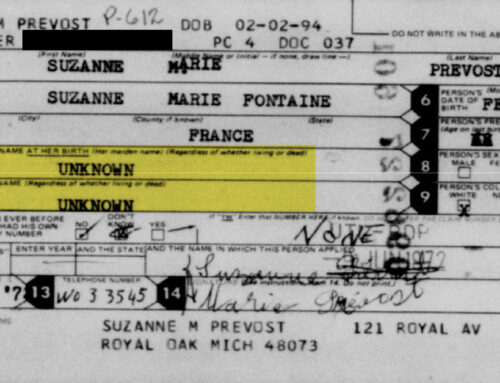

collecting DNA samples in Slovakia in 2004: AI-imagined (left) versus reality (right)

Genetic genealogist Diahan Southard recently asked a number of people involved in this field over the last 25 years to write about their recollections and thoughts for a book she was compiling, So Far: Genetic Genealogy, The first 25 years, 1999–2024. As an early adopter, I was surprised how many memories came flooding back, and struggled to get down to the requested word count, so I’m sharing a less-streamlined version here (with Diahan’s blessing).

free, downloadable book about the first 25 years of genetic genealogy

One aspect of genetic genealogy that never ceases to amaze me is how the media keeps covering it as if it were some newfangled, shiny object. But Diahan’s right. It’s been around for a quarter of a century. I was on board early, so I hope that genealogists’ inherent curiosity about the past will extend to our own history and that you’ll enjoy this personal-timeline, behind-the-scenes peek at genetic genealogy’s first ten years.

1999

You might be surprised to hear that I took my baby steps thanks to the U.S. Army. Hoping to identify soldiers missing from WWI, WWII, Korea, and Vietnam by tracing and obtaining DNA samples from living relatives, they launched a trial run, and I was invited to participate due to a fluke event.

The colonel in charge went to a Washington, D.C. area bookstore where I happened to be speaking that evening. Since my book was genealogical, she approached me after I was done. I would soon make a lasting impression by totaling my car in a telephone pole near her home (pro tip: never leave your car where a kid brother can get at it while you’re on a business trip), but that’s a story for another time.

After they tried a bunch of us on for size for about a year, two of us were awarded contracts. As an Army brat, I was delighted to make the cut. My father served in Vietnam, but he came home. So many other family members weren’t so lucky and have been left wondering for decades. This was a chance to at least make a dent by providing answers for some.

To date, 188 of the 1,717 soldiers I’ve investigated have been identified, and two others received the Medal of Honor posthumously. I’m grateful that “no man left behind” is so much more than a slogan, and to have had the opportunity to play a modest role in these homecomings.

2000

Sleuthing for the military opened my eyes to the possibilities of DNA and how it could be used to solve history mysteries, and I had just such a puzzle to solve in my own family involving all the Smolenyak families in the world (sometimes having a rare, unpronounceable name comes in handy!). We all hail from the same village, and I had traced the four lines back to the1700s, but the records petered out. We were serfs — not the kind to leave much of a trace. How would I ever be able to prove we were all related?

That’s why I was one of the first in line when Family Tree DNA (FTDNA) began offering Y-DNA tests in April of 2000. Since I had a long-established village association, the men I reached out to for DNA samples all agreed, and four of FTDNA’s first thousand kits were mine.

The results destroyed my hypothesis. Initially, I was devastated, but then it dawned on me that these DNA tests had saved me years of futile research. It had seemed so reasonable to assume we were related, so I would have devoted years and who knows how much money trying to prove it. I was wrong, but I was also hooked. What other riddles might DNA testing be able to solve?

2002

New technologies always face resistance, and genetic genealogy was no exception (I’m experiencing déjà vu with AI now). Some genealogists considered the use of DNA “cheating” or an attempt to shortcut traditional research, not yet grasping that conventional and genetic genealogy play very well together. Others opposed it for religious reasons (I still regret not being able to talk an organization I was associated with into accepting 150 free tests from National Geographic, and the main stumbling block was a vague, religious objection). And of course, there was the usual, generic wariness and suspicion about all things new.

Even though I was an established writer and speaker, this resistance meant that it took two years to get an article or talk accepted. Every other family history publication had already turned down “DNA Testing Dispels a Genealogical Myth” before the now-defunct Everton’s Genealogical Helper ran it that May. The piece won an award, so I began booking lectures and participating in Sorenson Molecular Biology Foundation (SMGF) blood-sampling events to encourage participation. The tide was beginning to turn.

2003

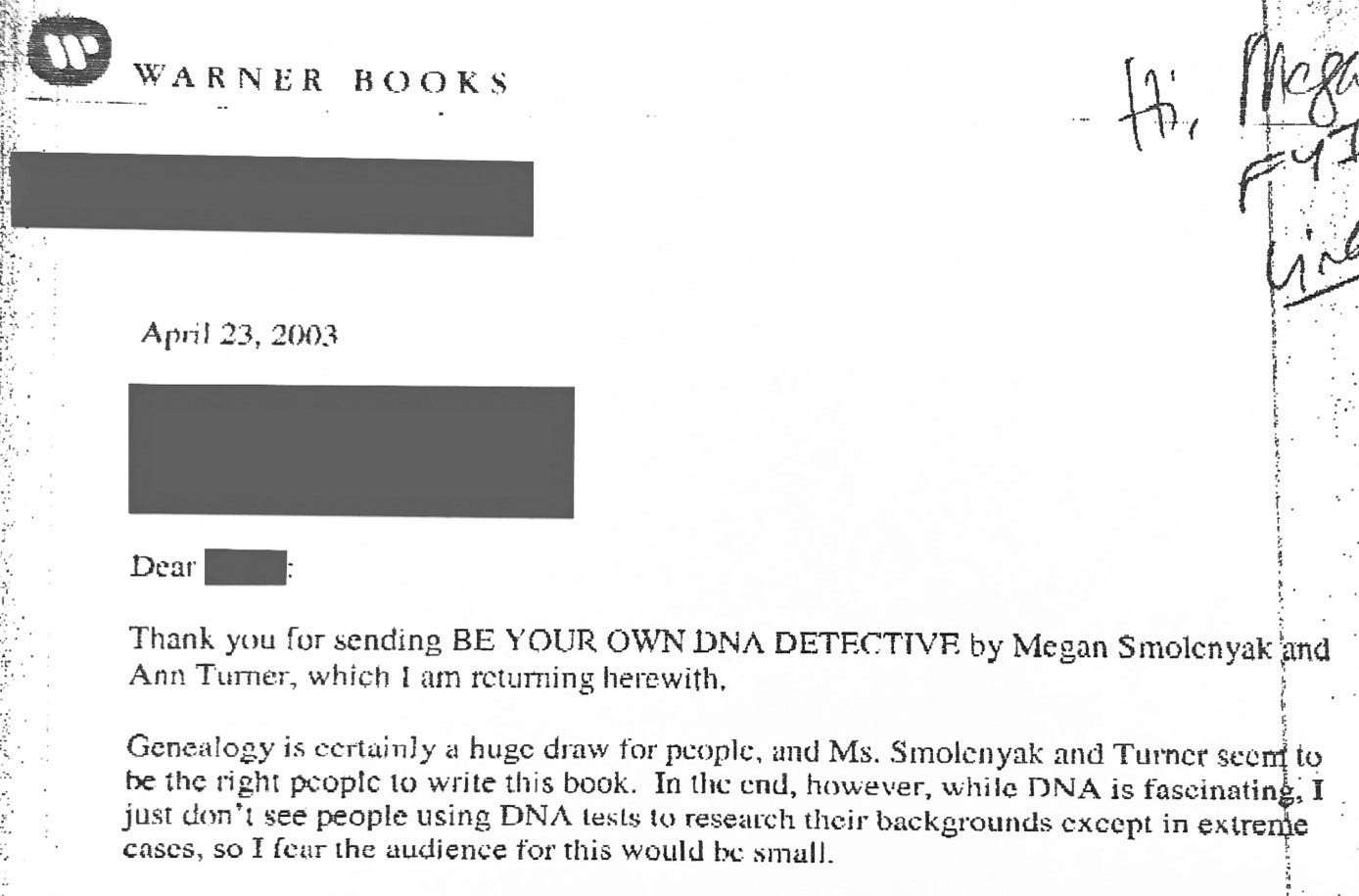

I had been eager to write a book about this amazing new tool almost from the beginning, but recognized that there wasn’t a sufficient audience yet. I held off for several years, but finally in 2003, succumbed to temptation and courted Ann Turner, M.D. to be my co-author. I already had a couple of books under my belt, so wrote a proposal and sent it off to my agent. Usually, she landed contracts within weeks, but not this time. All told, we received 37 rejections, one of my favorites being: “I just don’t see people using DNA tests to research their backgrounds except in extreme cases, so I fear the audience for this would be small.”

Finally, Rodale rolled the dice on the topic and the resulting book, Trace Your Roots with DNA, will soon celebrate its 20th anniversary.

2004

2004 started off well as I got to meet my co-author, Dr. Turner, about a week after we submitted our manuscript. Living on opposite coasts, we had written our book virtually. Coincidentally, we were both invited to a genetic genealogy brainstorming session hosted by a company in Utah even though no one had any clue that we knew each other.

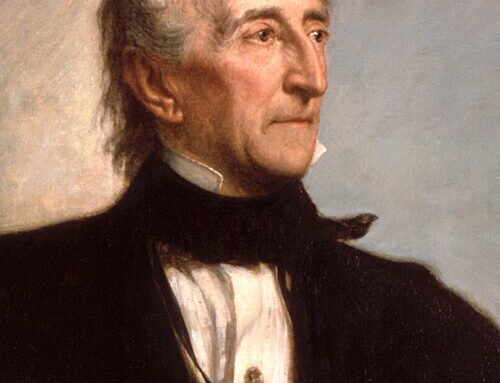

Later that year, my husband and I went to Osturňa, Slovakia to expand my Smolenyak surname study into a geographic one. The notion at the time was so novel that I recall others asking what I hoped to accomplish. I would respond honestly that I didn’t know, but thought the best way to learn was to experiment like this. Maybe it would be a waste of time or maybe not.

About a year later, National Geographic’s Genographic Project debuted, and my village project didn’t seem so strange anymore.

Although this was my third time to the Smolenyaks’ ancestral village, collecting DNA made it particularly memorable. Our undertaking was announced on the village’s loudspeaker system, men volunteered (the focus was on Y-DNA), and we visited their homes where we were rewarded with warm hospitality that often included slivovitz (plum brandy). My husband gamely took on the role of “designated drinker” since I was driving.

In October of that year, Family Tree DNA held the 1st International Conference on Genetic Genealogy, and all the early adopters were there. During a talk, I stated that genetic genealogy was unknown outside our enthusiastic bubble, a remark that spurred Katherine Hope Borges to establish the International Society of Genetic Genealogy to help spread the word.

2005–2007

I continued speaking and writing, and once SMGF switched from blood to mouthwash (they had to seek alternatives as too many feared needles), incorporated swishing sessions into my events!

swish party to gather DNA samples at one of my events

November of 2007 was a memorable milestone as autosomal testing was announced. Two companies — 23andMe and deCODEme (this aspect of this Icelandic company has since shut down) — launched within 24 hours of each other. It cost $1,000 which was daunting as I had to test everywhere to be able to speak and write about the topic, but the prospects were tantalizing!

Fortunately, I was a beta tester for 23andMe, so while I had to pay, my rate was subsidized. Since this was all so new, I conducted an experiment to test the tester. The claim was that they could tell you the relationship, if any, between people who tested with them. I wanted to see how true this was.

Osturňa once again came into play as it’s remote even today, so many with roots there are related in some way. I took advantage of this by selecting a combination of 15 Osturnites who would give me the maximum number of relationships to test among them. Using my village database, I looked for first cousins, first cousins once removed, second cousins, second cousins once removed, and so on. The intention was to compare known, paper-trail relationships with whatever the DNA testing said.

I thought I had been strategic, but the joke was on me.

Reviewing reports for these 15 hand-picked individuals, everyone mapped up tidily. First cousins showed up as first cousins and so on — with one exception. One of my own first cousins showed up as a second cousin. After entertaining theory after theory, I turned to Occam’s razor and realized that the explanation was the simplest and most obvious, but my built-in family biases had blinded me to it.

My father’s only brother was really his half-brother. They had the same mother, but different fathers. Once I figured out how to share the revelation with my father, I reached out to 23andMe. This turned out to be their first-ever family surprise, so I wound up explaining to 23andMe how their service had unveiled this secret. Countless others have since had the same experience.

2008–2009

Having worked on African American Lives and Faces of America withHenry Louis Gates, Jr., I took the opportunity to introduce him to 23andMe. I still remember how excited he was as we walked through his results, so it’s no surprise that genetic genealogy soon became a staple in Finding Your Roots thereby helping to popularize it with non-genealogists. Shortly after, in a hint of things to come, I assisted with my first criminal case, helping identify a murder victim.

This digest version of the first decade is admittedly somewhat sugar-coated because I’ve alluded to but haven’t lingered on the resistance we encountered in the early days. It’s easy to tuck aside because tempering this was the fact that we knew we were pioneers. How many ever get that chance? We were in a brand new playground making it up as we went along — both fun and gratifying. Please never forget that it was curious genealogists who first ventured into, gave shape to, and demystified much of this game-changing crossroads of science and history!

P.S. If you’re curious to hear more on the subject, you might want to watch this chat between Your DNA Guide, Diahan Southard, and yours truly.

Note regarding AI: While I make liberal use of AI to generate images to accompany my articles (and always identify them as such), it has not been used in any way to write this article — no brainstorming, drafting, editing, or any other aspect.

Leave A Comment