“It’s good to remember that we are a nation of immigrants, of hopeful wanderers. And we cannot know who is coming across our borders today whose story will add a significant page to the American story, who will work hard, who will raise a family, whose new blood will strengthen the good fabric holding our nation together.” – Bruce Springsteen

On January 1, 1892, 17-year-old Annie Moore from Cork, Ireland became the first immigrant to ever arrive at Ellis Island, so both Annie and Ellis Island celebrated their 125th anniversary on January 1, 2017. Of course, hopeful wanderers from other countries had been teeming to our shores by choice or force for centuries by then, but perhaps because 40% of Americans have at least one ancestor who arrived via Ellis Island, it has always been synonymous with immigration in a nation of immigrants.

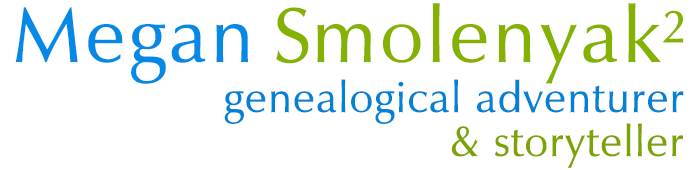

As the first, Annie became the poster child for immigration, which is why there are statues of her in both New York and Cork, and songs, books, awards, and even pubs sport her name and tell her story.

Almost from arrival, Annie suffered a series of indignities. No doubt appreciating the $15 in coins she received that day (a small fortune to her family), she was also overwhelmed by all the attention and used as a PR prop with the invention of a tale that it was her 15th birthday (she was 17 and her birthday was in May). And then, after her Kim Kardashian moment, she vanished from the pages of history into what was to be a sadly common, but somewhat hellish immigrant experience in the Lower East Side of Manhattan.

Annie and her family bounced from tenement to tenement as so many foreign born did back then, often in search of lower rents. At 21, she married Joseph Augustus Schayer and soon had the first of at least ten children she would bear over the next quarter of a century. Her first child died before his second birthday, but the next four were fortunate enough to make it to adulthood. And then things took a turn. Due to the family’s living conditions and likely to Annie’s own weakening health, only one of her final five children made it past the age of three, and the lone survivor died at 21. Even with the infant mortality rate in New York City at that time hovering around 34 per 100, it’s apparent that the Schayer family suffered more than most, and though we might want to convince ourselves that such high loss rates must have better equipped parents to cope, it’s not true. Frequency and familiarity did not render the death of a child any less painful than it is today.

The causes of death from her children’s records all point to the underlying culprit of poverty. Annie herself managed to make it to 50 and to Calvary Cemetery where my husband and I discovered that she had been buried without benefit of a tombstone in a plot with ten others. Still, her family was luckier than some as the child of a friend who couldn’t afford a grave is mixed in with Annie’s – a kindness immigrants often extended to others in need.

Megan Smolenyak with Annie’s unmarked plot at Calvary Cemetery, August 2006

It’s appropriate that Annie should have been the first at Ellis Island, as her story is so representative and American. In a precursor to what many of us wrestle with today, Annie numbed her sorrows with food – possibly at least in part with the macaroons her German-born father-in-law received a patent for – and struggled with her weight. Family lore has it that she was too large to be taken down the narrow tenement staircase when she passed, so was lowered out the window.

On a more positive note, as is so often the case with immigrants, her sacrifices led to greater opportunities for her descendants who have since flourished. At least one remained in the Lower East Side until this century, but most fanned out to New Jersey, Maryland, Wisconsin, Arizona, and elsewhere. They took on a variety of professions, worked their way up the economic ladder, and married others with diverse backgrounds so that Annie’s Irish genes have now blended with Hispanic, Jewish, Scandinavian, and more.

This is the pattern we see again and again: the immigrant struggles, but ensuing generations reap the benefits. So Annie’s tale is a fitting one for the poster child of the immigrant saga, but until I found them in 2006, most of her scattered descendants did not know about her because a usurper had taken her place, a discovery I tripped across while working on a documentary in 2002.

Descendants of another Annie Moore unwittingly asserted that their ancestor was Ellis Island’s first (a forensic analysis of sorts revealed that a commemorative plate, of all things, triggered a chain of events that allowed this error to germinate and spread), and curiously, no one troubled to verify the claim for years, even though the few relatives of the real Annie who knew of her all along had tried to raise the issue. Most likely this is because the other Annie’s story was a wild ride involving Western-migrating adventurers and revolutionary Irish kin – the way we like to see ourselves, I suppose – but it little reflected the harsh and selfless reality of most of our immigrant ancestors.

So the genuine Annie was a victim of historical identity theft by another Annie who wasn’t even an immigrant (the giveaway being her Illinois birth). By the time I found her resting anonymously under a bit of grass in a Queens cemetery, 114 years had passed since her arrival at Ellis Island and 82 since her death, so January 1, 2017 is the first milestone anniversary since we’ve known who she truly was.

And the timing is, well, interesting. Just as we should be celebrating Annie and Ellis Island’s 125th, we are instead in the midst of an anti-immigrant fervor. The attempt to otherize immigrants is gaining momentum and hearkens back to the days of Know Nothings, exclusion acts, and internment camps.

All of this makes now an especially relevant time to reflect on the Annie Moores in our own family trees – those pioneers who made a leap that so drastically altered the trajectories of their descendants’ lives for the better. In my own case, I think with gratitude of Ellen Nelligan, Peter Smolenyak, James Reynolds, Padonia Lukacz, and others whose choices and challenging lives have given me the opportunities I have.

Welcoming today’s Annies – those hopeful wanderers that Springsteen speaks of – requires generosity of spirit that doesn’t always come naturally, but it’s our legacy, and centuries of American history make it clear that the return on investment from this particular form of speculation is exceptional. Then again, maybe we should do it simply because it’s the right thing to do.

Featured Photo: (Left) – Annie and her brothers as commemorated in a statue at

Cobh Heritage Centre (credit: Katherine Borges) and

(right) – on the day they arrived at Ellis Island (colorized)

Leave A Comment